Catholic Virtues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

True & False Paths to Happiness - XXXVI

Mythical Men of the Transphere

In the literature that was in vogue in the second half of the 20th century, the word myth covers two overlapping paths. First, there is a marvelous history, evidently mythological, including many legends. Second, it includes a transcendent vision of things, which shows the symbolic aspect of the myth. This second component corresponds to something true in the notion of myth, in keeping with good doctrine. It is in this second legitimate sense that the word myth will be used here.

It is common knowledge that every stretch of civilization has its mythical men, who symbolize certain character traits and facts that did not really take place in their lives.

In other words, there is a way of looking at the mythical man that transcends the man himself. It corresponds to a conception often held about persons who personify what they symbolize. That is, they symbolize a higher reality that results from a vue de l'esprit – a product of our mind. This fact comes from the need we feel for the individualization or personification of certain principles or values.

In other words, there is a way of looking at the mythical man that transcends the man himself. It corresponds to a conception often held about persons who personify what they symbolize. That is, they symbolize a higher reality that results from a vue de l'esprit – a product of our mind. This fact comes from the need we feel for the individualization or personification of certain principles or values.

The mythical man is situated, therefore, in a transcendent sphere, a super-sphere, from which he communicates his transcendence to men. This transcendence is the myth. So then, the idea of myth brings with it the idea of a transphere.

Let us look at three outstanding examples of historical mythical personages.

Charlemagne, ideal model of a Catholic Emperor

When speaking of rulers, Charlemagne remains present even to our day. He is a model ideal. Kings everywhere felt obliged to follow this model. The model ideal of king ruled more than the flesh-and-blood kings who governed Europe.

When speaking of rulers, Charlemagne remains present even to our day. He is a model ideal. Kings everywhere felt obliged to follow this model. The model ideal of king ruled more than the flesh-and-blood kings who governed Europe.

Perhaps what the figure of Charlemagne has of the grandiose – even incomparably so – is the sublime idea he gives of a Catholic Imperator, a warrior, a half-prophet. He suggests such a high idea of an emperor that one can even catch a glimpse of an imperial power greater than he is, realized in a greater order than his: a perfect emperor who is not God, but a mere creature.

It would be a possible creature, but one who, in fact, never existed as currently imagined.

There are, therefore, two Charlemagnes: the historic Charlemagne and the Charlemagne of the transphere. One can imagines an unreal Charlemagne, but one who, at the same time, is more profound than the real Charlemagne. And this unreal Charlemagne still acts.

The memory of him generates consequences. The History of the world would certainly be something different if, after his physical death, the Charlemagne of the trans-sphere had also disappeared.

The legend ended by transforming Charlemagne into the Emperor of the transphere.

St. Joan of Arc, virgin and heroic warrior

One could also call St. Joan of Arc a heroine of the trans-sphere. Like it or not, she still weighs heavily in French History.

The combination of two virtues – chastity and heroism – is very beautiful. The greatest example of this conjunct we have is St. Joan of Arc, the heroic virgin and warrior born in Lorraine. Chastity is a virtue brimming with delicacy, filled with fragility. Courage is a virtue brimming with strength, willed with fearlessness. The joining of these two opposites forms a real marvel. They are like two parts of a spearhead that come together to form a very beautiful harmonic whole.

The combination of two virtues – chastity and heroism – is very beautiful. The greatest example of this conjunct we have is St. Joan of Arc, the heroic virgin and warrior born in Lorraine. Chastity is a virtue brimming with delicacy, filled with fragility. Courage is a virtue brimming with strength, willed with fearlessness. The joining of these two opposites forms a real marvel. They are like two parts of a spearhead that come together to form a very beautiful harmonic whole.

St. Joan of Arc is in a place where she is more or less untouchable. If someone wants to speak against her, not even all the sympathy of the media serves to mitigate the bad impression that detractor makes. Imagine that it becomes known that a man of letters is writing a series of articles against St. Joan of Arc... He is finished!

Writing a series of articles against St. Ignatius of Loyola, whom I admire perhaps more than St. Joan of Arc, does not disgrace the individual as much. But St. Joan of Arc, mounted on her horse with her breastplate and banner Mon Dieu et Saint Denis – with all that she becomes untouchable. No one can throw a lance at her without destroying himself. These are the designs of God Who chooses to give these various post-mortem earthly glories to the Blessed.

Dom Sebastião, able to resurrect the agonizing Middle Ages

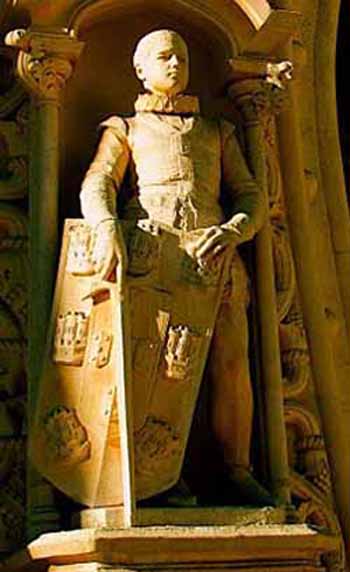

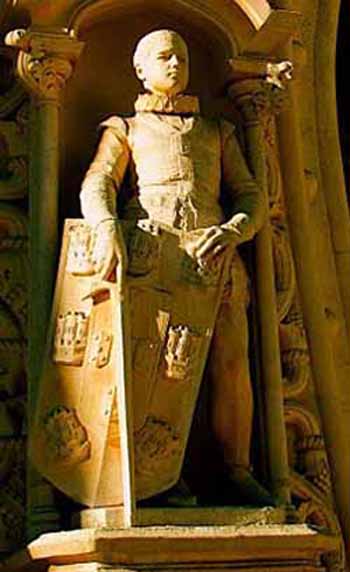

Dom Sebastião (1554-1578), King of Portugal, was certainly a figure of the transphere. He disappeared in the battle of Alcácer-Quibir in North Africa, and it was thought that he would return at any time to continue his historic mission.

This human symbol of Portugal is a name that I never pronounce without emotion because I have the impression that all the graces to which Portugal was called reposed on him: Dom Sebastião.

In some aspects Dom Sebastião looks more like an angel than a man. What figure in History dies and leaves behind a legend like the Sebastião legend?

This human symbol of Portugal is a name that I never pronounce without emotion because I have the impression that all the graces to which Portugal was called reposed on him: Dom Sebastião.

In some aspects Dom Sebastião looks more like an angel than a man. What figure in History dies and leaves behind a legend like the Sebastião legend?

The Portuguese understood in a nebulous way that he could not end like this and nourished a hope of something to come. Perhaps for lack of a better means of expression, they made the mistake of saying that it was Dom Sebastião who would return. But what they really had was a confidence that the work begun by Dom Sebastião would not end and would one day recommence. Portugal had the nobility to recognize in Dom Sebastião the King of its dreams.

Like all the other nations in Europe, Portugal was already beginning to be scarred by the Renaissance. But something fundamentally anti-Renaissance flourished there. When that King would have returned from Africa, his forehead shining with the glory of many, many victories, after he would have extended the power of Portugal across North Africa, at that Europe starting to die, a medieval Prince would have shined. The honor of the dying Cavalry would have flared up again; the thesis that temporal power exists for the service of the spiritual power would have shined forth again, and before this magnificent human type the defiled human types that the Renaissance applauded would have paled.

In Alcácer-Quibir there was a Virgin King, a model of Catholic virility, a model capable of resurrecting the agonizing Middle Ages. Then this man died in a mysterious way.

The Portuguese dreamed of that Dom Sebastião would return, but for Portugal something incomparably higher came: Our Lady came. The Virgin King did not come, but the Virgin of Virgins did. And just as Portugal should have given a message to the world in the person of Dom Sebastião at the time of the Renaissance, Our Lady, assuming the Portuguese territory as a throne, gave the world the message of Fatima.

It was not a message of nostalgia, but one of warning, a message of reproof, a message of hope. A message followed by mystery, like the mystery here that we could call the myth of Dom Sebastião.

There is a mystery here: a Queen who descends from Heaven, a hope that goes beyond the limits of all hope. All of this constitutes the link between the death of Dom Sebastião and the appearance of Our Lady in Fatima.

Continued

It is common knowledge that every stretch of civilization has its mythical men, who symbolize certain character traits and facts that did not really take place in their lives.

A transcendent sphere that represents a higher reality

The mythical man is situated, therefore, in a transcendent sphere, a super-sphere, from which he communicates his transcendence to men. This transcendence is the myth. So then, the idea of myth brings with it the idea of a transphere.

Let us look at three outstanding examples of historical mythical personages.

Charlemagne, ideal model of a Catholic Emperor

Charlemagne, the Emperor of the transphere

Perhaps what the figure of Charlemagne has of the grandiose – even incomparably so – is the sublime idea he gives of a Catholic Imperator, a warrior, a half-prophet. He suggests such a high idea of an emperor that one can even catch a glimpse of an imperial power greater than he is, realized in a greater order than his: a perfect emperor who is not God, but a mere creature.

It would be a possible creature, but one who, in fact, never existed as currently imagined.

There are, therefore, two Charlemagnes: the historic Charlemagne and the Charlemagne of the transphere. One can imagines an unreal Charlemagne, but one who, at the same time, is more profound than the real Charlemagne. And this unreal Charlemagne still acts.

The memory of him generates consequences. The History of the world would certainly be something different if, after his physical death, the Charlemagne of the trans-sphere had also disappeared.

The legend ended by transforming Charlemagne into the Emperor of the transphere.

St. Joan of Arc, virgin and heroic warrior

One could also call St. Joan of Arc a heroine of the trans-sphere. Like it or not, she still weighs heavily in French History.

The Maid of Orleans, a myth impossible to destroy

St. Joan of Arc is in a place where she is more or less untouchable. If someone wants to speak against her, not even all the sympathy of the media serves to mitigate the bad impression that detractor makes. Imagine that it becomes known that a man of letters is writing a series of articles against St. Joan of Arc... He is finished!

Writing a series of articles against St. Ignatius of Loyola, whom I admire perhaps more than St. Joan of Arc, does not disgrace the individual as much. But St. Joan of Arc, mounted on her horse with her breastplate and banner Mon Dieu et Saint Denis – with all that she becomes untouchable. No one can throw a lance at her without destroying himself. These are the designs of God Who chooses to give these various post-mortem earthly glories to the Blessed.

Dom Sebastião, able to resurrect the agonizing Middle Ages

Dom Sebastião (1554-1578), King of Portugal, was certainly a figure of the transphere. He disappeared in the battle of Alcácer-Quibir in North Africa, and it was thought that he would return at any time to continue his historic mission.

Dom Sebastião, the Virgin King the people would not allow to die

The Portuguese understood in a nebulous way that he could not end like this and nourished a hope of something to come. Perhaps for lack of a better means of expression, they made the mistake of saying that it was Dom Sebastião who would return. But what they really had was a confidence that the work begun by Dom Sebastião would not end and would one day recommence. Portugal had the nobility to recognize in Dom Sebastião the King of its dreams.

Like all the other nations in Europe, Portugal was already beginning to be scarred by the Renaissance. But something fundamentally anti-Renaissance flourished there. When that King would have returned from Africa, his forehead shining with the glory of many, many victories, after he would have extended the power of Portugal across North Africa, at that Europe starting to die, a medieval Prince would have shined. The honor of the dying Cavalry would have flared up again; the thesis that temporal power exists for the service of the spiritual power would have shined forth again, and before this magnificent human type the defiled human types that the Renaissance applauded would have paled.

In Alcácer-Quibir there was a Virgin King, a model of Catholic virility, a model capable of resurrecting the agonizing Middle Ages. Then this man died in a mysterious way.

The Portuguese dreamed of that Dom Sebastião would return, but for Portugal something incomparably higher came: Our Lady came. The Virgin King did not come, but the Virgin of Virgins did. And just as Portugal should have given a message to the world in the person of Dom Sebastião at the time of the Renaissance, Our Lady, assuming the Portuguese territory as a throne, gave the world the message of Fatima.

It was not a message of nostalgia, but one of warning, a message of reproof, a message of hope. A message followed by mystery, like the mystery here that we could call the myth of Dom Sebastião.

There is a mystery here: a Queen who descends from Heaven, a hope that goes beyond the limits of all hope. All of this constitutes the link between the death of Dom Sebastião and the appearance of Our Lady in Fatima.

Continued

Posted December 13, 2021