Movies & Shows

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Movie & Book Comparison - Part I

Flaws of the Four Sisters in Little Women

novel by Louisa May Alcott, NY: Scholastic Inc, 2000

Elizabeth A. Lozowski

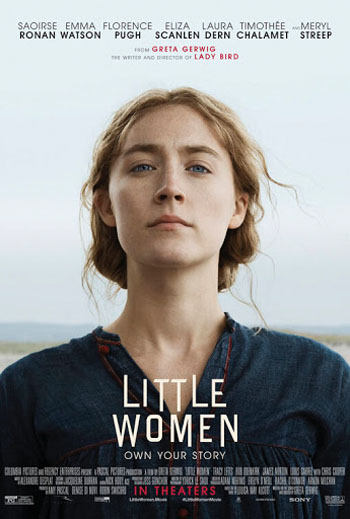

The 2019 release pushes feminism as far as it can in Alcott's main character Jo

The story, set in the 19th century, is quite simple: Based on her own family life, Alcott follows the lives of the March sisters, Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy, who become friends with their wealthy neighbors, the lonely lad Laurie and his crusty grandfather, Mr. Laurence.

Greta Gerwig, director of the recent film, knew how to take full advantage of the story line, pushing her feminist agenda by showing how pre-liberated conventional women were “oppressed” and unfulfilled. It is against this “oppression” that the March sisters, especially Jo and Amy, rebel.

Indeed, even in the book (written in 1868), the March girls and their mother “Marmee” are rather unconventional and free-thinking, as their prudish Aunt March frequently points out. The father – away at war for half the novel – has no paternal presence in the home, even after he returns. As a consequence, the March family is quite “modern” with the women running the household where “freedom and indulgence” reign supreme. (Little Women, chap. 19, p. 218) In this regard, the book opens the door for the liberties Gerwig takes with her adaptation.

What is most striking about the 2019 movie is the lack of personality of the actresses and actors. Their acting skills are not necessarily poor, but nothing endears them to the viewer or gives them a sense of uniqueness. Like most of the stars of our day, they lack the charisma, charm and vivacity of the personalities of Hollywood in days past. Comparing the recent release with the 1949 version of Little Women, the actors in the new film do not measure up. The latest “little women” lack the capacity to be anything but those empty people they are.

Rambunctious, spontaneous behavior incongruent with 19th century women

In the movie the March house is disordered and cluttered, contrary to the way it was run in the book, where each girl is portrayed having her designated chores to fulfill each day. The girls undress in front of Laurie, chatter, giggle, scream and jump all over each other like a pack of animals while their non-judgmental Marmee laughs with them, giddy and trying to appear young like her daughters. Jo and Laurie do modern dance movements together, fool around like two “buddies,” hit each other, and act like today's teenagers.

Additionally, the language in the movie is very modern: short, casual and unrefined, different from the book where the tone is more elevated. However, even in the book we find an openness and informality abnormal for the era - which is precisely what makes the March home so "unique" and unconventionally American. In Gerwig's film, these revolutionary tendencies simply come to their fruition.

To demonstrate these tendencies, I will analyze each character as presented in the book, and then explain how the film brought them to their radical conclusions.

Jo: From independent tomboy to arrogant feminist

Jo, the second eldest March sister and main character of the story, is a tomboy who disregards all social graces and manners. She is proud to flout conventions and say what she thinks with a frankness that is blunt and fiery. She despises the restraints placed on women, declaring she does not care what others think as she whistles, runs, yells and uses vulgar language.

A revolted Jo who wants to look and act like a man

It is not hard to see how such a feminist character earns the sympathy of modern women. The girls who admired Alcott's Jo in their youth raised daughters to be as modern and liberated as Gerwig’s Jo.

In the movie, Jo, played by Saoirse Ronan, is revolting and ambitious, without a spark of the amiability, natural virtue or character she displays in the book. Ronan uses her character to resonate with every modern woman, rejecting everything feminine, wearing men’s vests, ties and hats, negotiating with the book publisher, and delivering dramatic feminist speeches.

But, even though much of this feminist banality is not in the book, it is not hard to imagine Alcott’s Jo March uttering the same words. Every feminist tendency present in the book's Jo comes to its final conclusion in this modern film.

Meg: feminine yet superficial

Meg is the eldest and most mature of all of the March sisters. She has a feminine grace and sweetness which is commendable, but her vice is superficiality. Loving beautiful things and a life of pleasure, she desires to appear elegant and, on this account, hates being poor. Jo’s behavior scandalizes her as they attend parties and concerts together, but she tolerates it and loves Jo despite her faults because she follows Marmee's teaching that the most important thing is to accept people as they are.

A feminine but somewhat giddy Meg

Emma Watson’s portrayal of Meg, while evoking a feminine gentleness that makes her the most likeable of all the sisters, lacks the maturity and elegance the character has in the book. At times she acts giddy like a modern girl, fitting in well with her more radical sisters.

Truly, there is not much Gerwig could change about Meg’s character, because she never desired independence, like a feminist. Meg is used to promote the idea that every woman’s dreams should be accepted – whether it be to have a family or to have a career. As long as everyone tolerates each other and no one dictates to another her place, the world will be a happy place, according to this liberal mentality.

Amy: from proper lady to arrogant brat

Amy, the youngest sister, is vain and spoiled, wanting to impress everyone and be the center of attention. Her vanity leads her to imagine herself the perfect lady as she tries to appear grown-up and sophisticated. As the book Amy grows older, she matures and becomes a fine lady because she learns to overcome her selfishness by making sacrifices for others.

From sulky youngster to modern woman who achieves her goal to dominate

Her ambitions to be either a famous artist or an important lady of a wealthy household dominate her actions, and she uses her feminine charm to her advantage, enjoying the power she can exert over men. Although in the end Amy marries Laurie, she does not lose her independence or her ambition, for the two share equally in running the household, and, as Laurie admits to Jo, Amy rules her husband.

The actress Florence Pugh portrays Amy without the natural charm she exudes in the book: As a child she is whiny and throws temper tantrums and as a young woman she is revolted and cynical. Pugh’s hoarse, low voice and spontaneous mannerisms give no hint of feminine grace or sweetness.

The film takes the most liberties with Amy, creating new feminist lines for her to bewail the sorry plight of women: “As as a woman, there’s no way for me to make my own money. Not enough to earn a living or to support my family, and if I had my own money, which I don’t, that money would belong to my husband the moment we got married. And if we had children, they would be his, not mine. They would be his property, so don’t sit there and tell me that marriage isn’t an economic proposition, because it is.”

Even though Alcott’s Amy certainly never bemoaned her fate as a woman, her unwomanly ambitions could well lead to Pugh’s Amy. The marriage between Amy and Laurie in the movie completes the feminist dream, for she thoroughly controls the marriage, bossing Laurie around as he blindly follows like a puppy.

Beth: from a sweet tolerant child to a dull manikin

Beth is the second youngest and most respectable of all of the characters. Innocent and shy in the book, she is always willing to make a sacrifice and do good deeds to help others. Her one wish is to stay at home helping her family. Yet, Beth is not a character with real virtue, for she does these things to make others happy and not for the love of God.

Jo casually drapes her arm

around her favorite sister Beth

In this regard, she is more dangerous than any of the other characters, because she is the likeable American liberal, the perfect mediator between the old ways of being and the emerging feminism in Jo, her favorite sister.

On the contrary, Gerwig’s Beth has no personality; her blank gaze, dull expressions and flat voice are not the endearing Beth of the book, but rather a type of unchanging manikin. Nothing in her way of being suggests generosity, the trait she is supposed to express. Her voice, like Amy’s, is low and monotonous. No sweetness or innocence manifest themselves in her bearing or speech. I believe this is because the modern world does not understand innocence and can never portray it well.

Additionally, Beth has no real role to play in the movie: Jo’s behavior is no longer shocking or misunderstood, and a mediator to soothe the reactions against Jo is no longer necessary.

The 1949 film: a more realistic

picture of the March family & home

Posted June 26, 2020

______________________

______________________