|

Movie Reviews

José Sánchez del Rio,

Martyr for Christ the King

For Greater Glory reviewed by Margaret Galitzin

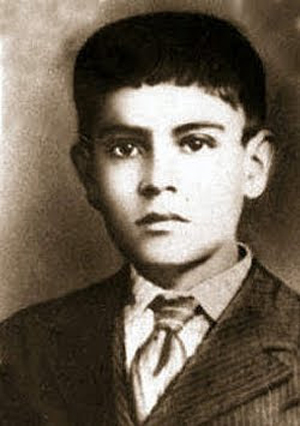

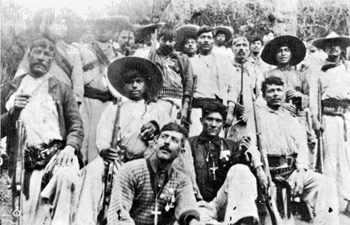

Jose at right, was a Cristero flagbearer - but not for Gen. Gorostieta |

One of the best consequences of the movie For Greater Glory about the Cristeros is the story of their young martyr José Sánchez del Río that has come to the fore. The film follows the characters of Gen. Enrique Gorostieta (Andy Garcia), an atheist who is asked by the Cristeros to organize them and lead their army, and Blessed José Sanchez del Rio (Mauricio Kuri), a Mexican boy who was martyred during the civil war.

The story of this 14-year old youth is moving and well presented although, in some points, historically inaccurate. For example, José never met General Gorostieta – he actually fought under the command of local General Rubén Guízar Morfin. I believe many readers would like to know the facts of José’s story to have the “real picture” of the life of this valiant youth so they can compare them to the movie’s presentation. His history follows.

“I want to be a Cristero”

José Luis was born on March 28, 1913, in the town of Sahuayo, Michoacan, the third of the four children of the cattle ranchers Señor Macario Sánchez and Señora Maria del Río. The Sanchez family was one of the leading families of the area, known to be virtuous and strong Catholics. José was a good boy with a natural piety, an obedient and loving son. At his First Communion at age 9, José received a special grace and began to be more serious about his religion. He had a strong devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe and said his daily rosary with care.

This was the time of the fierce persecution of the liberal Calles government against the Catholic Church. Jose was 12 when the Cristero War broke out, the peasant uprising that fought in defense of the Catholic Faith. The region where Jose lived was a stronghold of the Cristeros from the beginning of that counter-revolutionary movement. Idealism and zeal for the fight were in the very air they breathed.

An authentic photo of Jose Luis Sanchez del Rio |

Jose’s two older brothers, Macario and Miguel, had left in 1926 to join the Cristeros forces under the command of General Ignacio Sánchez Ramírez, and their younger brother longed to join them.

At first his parents would not give permission for him to go. But José persisted, “Quiero ser Cristero!” [I want to be a Cristero!] To his mother’s protest that he was only 13 and too young, he answered, “Mamá, it has never been easier to earn Heaven as now.”

In the end, she could argue no more, but the Cristero commander in their town, Sahuayo, refused the boy's appeal to enlist. So, he made his way some 20 miles to the next town, Cotija, where he presented himself to the Cristero commander, Prudencio Mendoza.

"What contribution can so small a boy make to our army?"

"I ride well. I know how to tend horses, clean weapons and spurs, and how to cook and fry beans."

Mendoza was inspired by the boy's resolution, and placed him under the local commander General Rubén Guízar Morfin. From the beginning, José showed himself ready to serve willingly and readily, earning the respect and admiration of his fellow Cristeros.

Impressed by José's religious fervor and intrepid spirit, Morfin made him bugler and flagbearer of the troop. His job was to ride alongside the general in combat, carrying his battle standard and delivering the general's orders with his horn.

‘My general, here is my horse’

On February 6, 1928, Morfín Guizar’s Cristeros engaged in a fierce battle with the federal forces in the vicinity of Cotija. The Cristeros were outnumbered ten to one, and had run out of ammunition for their rifles. The Cristeros were in retreat – a rare thing for these valiant forces –when the horse of General Morfin Guizar was shot dead.

Seeing this, José jumped from his own mount and offered it to his chief, saying these words, “My general, here is my horse. Save yourself. If they kill me, I am not needed, but you are.”

Helping Morfin up into the saddle, José delivered a hard swat across the backside of the horse and sent it galloping away. José, however, was captured along with other Cristeros, including a friend Lazarus, a few years older than he.

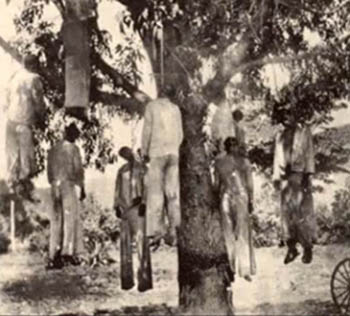

Normally, the federal soldiers shot all the Cristeros they captured alive or hung them from trees in the square or on telegraph poles. But this was not the fate of José and Lazarus. Because of their youth, they hoped to frighten and intimidate the youths into abandoning the Cristero fight.

The soldiers took the boys and marched them, their hands tied behind them, to Cotija. Along the way they ridiculed and gave them blows, saying, “Let’s see what kind of men you are.”

‘I believe I will die soon’

In Cotija, they were taken before the Federal General Callista Guerrero, who told the boys they were too young to know what they were doing: “Who told you to fight the government? Don’t you know that is s a crime paid for with death?”

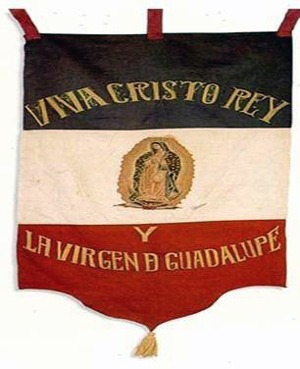

Cristero banner - Long live Christ the King and the Virgin of Guadalupe |

He ordered a firing squad be drawn up, and then offered the youths an escape: their freedom if they would enlist with the government troops.

José quickly responded, “Death before that! I am your enemy. Shoot me!”

The General ordered the boys to be locked in a jail in Cotija. In that dark and stinking dungeon, Jose asked for paper and ink to write his mother, a letter that somehow managed to reach its destination. It reads:

“Cotija, Mich., Monday, February 6.1928.

“My dear mother:

“I was taken prisoner in combat today. I believe that I am going to die very shortly, but it does not matter, mamá. Resign yourself to the will of God. I die happy, because I die in the ranks of Our Lord.

"Do not be distressed about my death, which is my only worry. Tell my brothers to follow the example of their younger brother and do the will of God. Have courage and send me your blessing and my father’s.

"Give my greetings to all for the last time and receive the heart of your son who loves you and wanted to see you before dying.

“José Sánchez del Río.”

“I am ready for everything’

The next day, February 7, the two youths were transferred to Sahuayo, their native village, and came before the federal deputy, Rafael Picazo Sánchez, who was the boy’s godfather. He presented José several opportunities to flee, first offering him money to go abroad, then proposing to send him to military school to pursue a government career. He need only reject the Cristero cause. José unhesitatingly refused.

The two boys were assigned to be jailed in St. James Church, a makeshift prison where horses were stabled and the deputy kept his fighting cocks. José was indignant at this outrage to the house of God. That night he managed to untie his hands, and he spent part of the night wringing the necks of Picazo’s roosters. Then he lay down in a corner and fell asleep.

The next day, February 8, when the deputy heard of the slaughter of his cocks, he became furious and confronted José angrily. The boy responded, “The house of God is for prayer, not to shelter animals.”

The Federal soldiers hung the martyrs from telegraph poles, above, or from trees in villages squares, below

|

Picazo threatened him, asking him if he was ready for what was to come.

Jose answered without hesitation: “Since I took up arms, I have been ready for everything. Shoot me! For then I will be before Our Lord and I will ask him to chastise you.”

Hearing this response, one of Picazo’s aides gave José a blow to the face that knocked out several teeth. Without a doubt, the fate of José and Lazarus was now sealed.

On that morning, Wednesday February 8, Jose’s Aunt María brought the boys lunch, but the anguished Lazarus had no appetite. Jose, however, was not disheartened and encouraged his friend, “Courage, Lazarus, let us eat well. They will give us time for everything and then shoot us. Don’t give up. Our sufferings will last just a blink of eyes.”

At 5:30 p.m., they took Lazarus to be hanged in the main square and obliged Jose to witness the execution. They let his body hang a few minutes then cut him down, thinking him dead, and dragged him to the nearby cemetery where they left the body. But Lazarus was not dead. Lazarus – truly aptly named – revived and escaped with the help of a sympathetic guard. A few days later, he rejoined the Cristeros.

The federal officials had hoped to frighten José so that he would reject the Cristero cause. But he faced the butchers courageously and told them to kill him also. Still hoping to change his resolve, they returned him to the church-prison and locked him in the baptistery. From its small grilled window, which still can be seen today, some of the people of the village spoke with the boy. They reported he was composed and spent his time praying the rosary and singing hymns.

Meanwhile, José’s father was desperately trying to raise the ransom put on the head of his son by General Calles Guerrero. The amount was $5,000, a fortune at that time. The grieving father could not raise such a sum, and instead offered his house, furniture, and everything he owned. He realized the futility of his efforts when Deputy Picazo sent him away, shouting: “Get out of here. With or without the money, I’ll send him to be killed under your very nose.”

When José heard about his family’s efforts to free him, he asked that they not pay a single penny of ransom. He had already offered his life to God and was resigned to death.

By this time, all the people of Sahuayo knew what was happening and were praying for José and his family. Tension over his fate was rising by the hour.

‘The moment I have so greatly desired has come’

On Friday, February 10, around 6 p.m., they took José from the parish church to the makeshift barracks across the street and announced his death sentence. The boy immediately asked for paper and ink to write his Aunt María to thank her for her unconditional support and to ask her to have his Aunt Magdalena bring him the Viaticum that evening before he would be executed. He wrote:

“Sahuayo, February 10, 1928.

“Mrs. María Sanchéz de Olmedo

“Dearest Aunt,

“I am sentenced to die. At half past eight tonight the moment I have so greatly desired will come. I thank you and (Aunt) Magdalena for all your kindnesses to me. I am unable to write mamá: I ask you the favor to write to her. Tell Aunt Magedalena that I managed to arrange that they permit me to see her for the last time and I believe that she will not refuse to come (to bring Holy Communion) before the martyrdom.

"Give my greetings to all. Receive as always and for the last time the heart of your nephew who loves you dearly …

"Cristo vive, Cristo reina, Cristo impera y Santa María de Guadalupe.

“José Sánchez del Río, who dies in defense of the Faith”

‘Viva Cristo Rey! ¡Viva Santa María de Guadalupe!’

At 11 p.m., the hour of martyrdom arrived. Believing that torture would change the mind of the boy, the government soldiers flayed the skin from the soles of his feet, thinking that José would weaken and cry out for mercy. But they were wrong. As the sharp pain seared through his body, José thought of Christ on the Cross and offered him everything, all the while shouting ‘Viva Cristo Rey!’

Whole families - like Jose's - were dedicated to the Cristero cause |

Then the soldiers, hurling insults at him and giving him blows forced him to walk barefoot with his injured feet through the cobblestone streets toward the cemetery. Along the way, some of the soldiers cut his body with a machete until he was bleeding from several wounds.

At times they stopped him and said, “If you shout, ‘Death to Christ the King’ we will spare your life.” Jose would only shout, “I will never give in. Viva Cristo Rey! Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe!”

When they reached the cemetery, the soldiers stood the boy before a newly dug hole, his grave. The executioners riddled his battered body with bayonet stabs. At each stab, the boy cried out louder, “Viva Cristo Rey!”

Then the commander of the guard addressed the youth, cruelly asking if he wanted to send a message to his father. To this José replied without yielding, “That we will see each other in Heaven. Viva Cristo Rey! ¡Viva Santa María de Guadalupe!” These were his last words.

The captain drew his pistol and shot him in the head. José fell into the pit. It was half past eleven on Friday, February 10, 1928. He was 14-years-old.

A rich and long lasting legacy

The spectators stood in shock and silence. The only sound was the soft sobbing of Jose’s mother, who had accompanied him to the last moment, praying for courage for her son to die well. The villagers had never seen anything like this. Even the federal soldiers, some who were reluctantly obeying the orders, were amazed at such courage.

Many boys like Jose took up arms in the Cristero ranks - prepared to give their lives for Christ |

The guard hastily covered the boy’s body, burying him there like an animal without a coffin or shroud. The life was extinguished in the body of José Luís Sánchez del Río, but his soul had entered into eternal glory.

In his short life, he left an immense legacy. He had given his countrymen and fellow Cristeros a shining example of courage and fidelity to their holy cause. He had shown so great a courage that those who witnessed it believed that only Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself could have given a mere boy the strength to endure such suffering.

Some years later, his remains were exhumed and were laid in the Crypt of the Martyrs in the Church of the Sacred Heart in the town where he was born. In 1996 they were transferred to the Parish of St. James, where he had been detained the day preceding his martyrdom. The day of his beatification, along with 11 other Cristero martyrs, was November 20, 2005.

The major flaw of the movie For Greater Glory

We should not imagine that the case of José del Sanchéz was an isolated one. Many youths, like José, were eager to take up arms as Cristeros and to give their lives for Christ the King. One old Mexican man, recalling those days, tells how his mother Mrs. Petra Rivas, who risked death herself to take clothes and food to the soldiers regularly, actually instructed him to join the Cristero cause.

“But what if I die and never see you again?” he asked. “Then you will be a martyr for Christ and I will see you in Heaven, where you will be waiting for me,” she replied.

The Cristeros were fighting for the one true Faith, not for revolutionary "religious liberty" |

These soldiers for Christ – young and old – had a clear idea of what they were fighting for: the restoration of the rights of the Catholic Religion and the reinstatement of Christ as King of society. They would be confused, I am sure, by the notion of revolutionary religious liberty being touted as their aim, which is the most serious flaw of the movie For Greater Glory.

Freedom of religion for all, including Protestants and pagans, and separation of Church and State – these were the revolutionary ideas the counter-revolutionary Mexican Catholics had resisted since the bloody Masonic–inspired revolution had established the first Constitution in 1910. The “religious freedom” they were defending was not the revolutionary brand being promoted today, but freedom of religion for the one and only true Faith and the restoration of Christ as King of society.

This is affirmed in the last letter of José to his aunt, when he wrote that he was happy to give his life - not for religious freedom - but “for Christ the King and the Faith.”

Relics and a wax figure of José Sanchez del Rio in St. James Church in Sahuayo |

Sources:

Madera de Héroes, Semblanza de algunos héroes mexicanos de nuestro tiempo by Luis Alfonso Orozco, La Libreria Católica, 238 pp.

Biografia: José Sanchez del Río, http://www.beatificacionesmexico.com.mx/web/jose.php

Posted June 18, 2012

Related Topics of Interest

A Prayer of the Cristeros of Jalisco A Prayer of the Cristeros of Jalisco

The Cristeros I: The Spaniards Land in Mexico The Cristeros I: The Spaniards Land in Mexico

The Cristeros II: Long Live the Virgin of Guadalupe! The Cristeros II: Long Live the Virgin of Guadalupe!

The Cristeros III: Hildalgo Raises the Standard of Revolt The Cristeros III: Hildalgo Raises the Standard of Revolt

The Cabalgata of Christ the King The Cabalgata of Christ the King

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Movie Reviews | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|