Book reviews

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Slavery in the North & South -

Myths & Reality

Book review of The North, The South & Slavery, Book II, by Adam S. Miller,

Monrovia, MD: Tower of David/Marian Pub., Inc., 2015, 120 pp.

Monrovia, MD: Tower of David/Marian Pub., Inc., 2015, 120 pp.

In the second volume of his series on the South, Adam Miller takes on the controversial topic of the slavery in the United States. Miller’s belief that the South has been unjustly vilified by the Northern victors of the war leads him to expose the many distortions surrounding the institution of slavery. He does not seek to justify slavery as it is popularly understood, but rather attempts to expose and refute the myths and misrepresentations surrounding it.

From the start he makes a positive Catholic assertion: Every man is a slave, either to sin or the Will of God. Only those who humbly submit themselves to the Divine Will, above their own will, can be truly free. Catholically speaking, humility and obedience are praiseworthy virtues, and there are numerous examples of saints who were slaves during their time here on earth.

Remember that slavery existed both in the Old Testament and at the time of Our Lord and received no condemnation, nor has the Church condemned slavery per se, but rather its abuses. Taking apostolic examples, the author also cites that St. Paul himself urged slaves to obey their masters.

He cites several Popes condemning the abuses of slavery, the slave trade, the unjust enslavement of persons, the separation of slave families and enslavement based on race. Further, slavery is only justified by the Church in conditions where a person is captured in a just war, as punishment for heinous crimes and being born into the state of slavery.

Pope Gregory XVI explicitly condemned the slave trade with the full support of the American Bishops of the South. Creation itself is hierarchical, though Miller stresses that as in all institutions, such as education, employment and marriage, there are instances that transgress the bounds of acceptability. No matter where one seeks there is the taint of fallen human nature.

Americans must further be aware, the author warns, that much of the modern conception of slavery comes from the warped and condemned teachings of equality and liberty espoused by the revolutionary thinkers of the 18th century. These revolutionaries redefined liberty, not as the freedom to do God’s Will, but as freedom from all authority outside oneself.

Americans must further be aware, the author warns, that much of the modern conception of slavery comes from the warped and condemned teachings of equality and liberty espoused by the revolutionary thinkers of the 18th century. These revolutionaries redefined liberty, not as the freedom to do God’s Will, but as freedom from all authority outside oneself.

Espousing ideas condemned by the Church, these men rebelled against the very order of God in their quest for self-governance. Such ideas have contaminated our society today and are in no small part responsible for the robotic repulsion to the idea of human slavery regardless of time or circumstance.

Having analyzed slavery from the Catholic perspective, Miller demonstrates, chapter by chapter, that slavery in America did not start with racism (the first slaves were Catholics and Irish), that the South was not wretched as reported, that the North practiced its own forms of slavery and that Northerners were often much more racially prejudiced than Southerners.

Hypocrisy of the North

The North, historically, had slaves just as the South, though it died out as economically unfeasible. The slave trade brought profits to the North and was perpetuated long after Popes condemned the practice. In the course of a few years Northerners imported far more slaves than were ever freed by such abolitionist movements as “the Underground Railroad.” Ironically, Southern backed legislation intending to end the slave trade was vigorously opposed by the North.

Contrary to the myth, the North was not racially tolerant. Most Northern abolitionists, including Abraham Lincoln, believed that blacks should be sent to live somewhere else, but few ever dreamed of allowing blacks to mingle in white society.

Contrary to the myth, the North was not racially tolerant. Most Northern abolitionists, including Abraham Lincoln, believed that blacks should be sent to live somewhere else, but few ever dreamed of allowing blacks to mingle in white society.

Many Northern States outlawed the black vote as late as 1867. Several imposed laws designed to prevent non-whites from settling. The American Colonization Society, an organization funded by the North, even sought to solve the “problem” of free blacks by sending them to Liberia.

Racism was so fierce that many blacks who had escaped slavery in the South were forced to go on to Canada to flee the race violence of white Northerners. French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville noted during his visit to the U.S that racial prejudice ran deep in the North. There, he said, whites outright refused to work alongside blacks, as was common for workers in the South.

When Lincoln declared the Emancipation Proclamation there was a spike in the desertions in the Northern army, with some officers even submitting their resignation. Many had been told the war was to “preserve the Union,” and riots broke out in several Northern cities to protest a war for liberating blacks. Blacks who fought in the Union army did not even receive the same pay and benefits as their white comrades. Lincoln himself can be frequently found espousing ideas of racial purity and the inferiority of blacks.

Slave of the South, slaves of the North

After exposing the prejudiced treatment of blacks in the North, Miller devotes several chapters to comparing the condition of the average Northern worker with the average Southern slave. In this way the reader gets a more contextual understanding of slavery as it existed in 19th century America and the hardships endured by the working man.

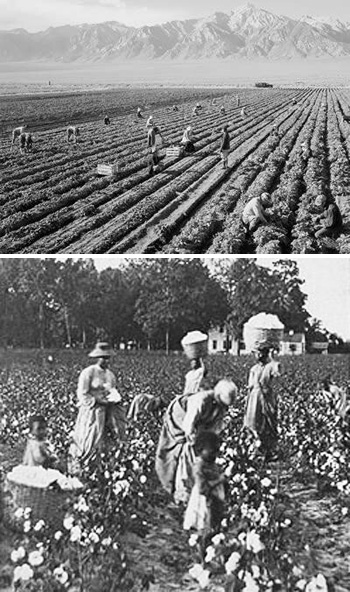

Northern factory owners routinely paid a barely livable pittance and, if injury or sickness would occur, the worker would be thrown out. Many factories employed women and children under abusively small wages. White workers, including children, often worked 16 hour-a-day shifts locked in their factories performing repetitive tasks with dangerous machinery, leading to workplace death tolls in the tens of thousands every year.

Northern factory owners routinely paid a barely livable pittance and, if injury or sickness would occur, the worker would be thrown out. Many factories employed women and children under abusively small wages. White workers, including children, often worked 16 hour-a-day shifts locked in their factories performing repetitive tasks with dangerous machinery, leading to workplace death tolls in the tens of thousands every year.

The family cell was undermined, as fathers and mothers could be kept away from home for weeks or months at a time, if they weren’t crowded into tenements surrounding the factory complexes. At other times workers were obliged to live in “company towns” where they were provided shacks for housing and were paid in money that was only good at the exorbitantly expensive company store.

The massive industrial system of the North deprived workers of just wages, reduced supposedly free men, women and children (some of whom were literally kidnapped from England and brought to America to work) and discarded those who could no longer turn a profit. It was slavery in all but name.

By contrast Miller examines the condition of the average slave in the South. Contrary to some deeply held myths, many slaves made money, and it was common for slaves to be allotted plots of land where they could grow their own crops for market. In some cases slaves saved up fair amounts of wealth and there were even slaves, as in the case of Simon Phillips, who loaned money to their masters when the owner was in financial distress.

Those who owned few slaves and were not financially well off worked alongside their slaves day in and day out, a practice that was abhorrent to white Northerners. It was also common for slaves to be given training in specialist skills, which would serve them well if they were freed or hired out. In this way a large plantation could resemble a medieval estate, with an amiable and hierarchically ordered self sustaining society.

While relations between master and slave were often quite positive, the positions of abolitionists were frequently delusional disingenuous. One slave, Harrison Berry, was so fed up with such Northern distortions that he wrote a book defending slavery and the South. This not only shocked Northerners who believed that slaves were universally miserable, but it destroyed a further myth by showing a slave could write.

This and other works exposed the exaggerations and misrepresentations in such popular, though unrealistic, titles as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Later, the 1930’s slave testimonies, collected by the American government, also show that less than 30% of the interviewees, elderly blacks who still remembered being slaves, had anything negative to say about their masters at all. Some even reported living in better conditions than were available in the ‘30s.

Black confederates

As a final blow to the many racially charged myths surrounding the South, Miller goes on to cite that there were many blacks who actively supported the Southern cause. The numbers in support of this controversial position show that an estimated 60,000 – 93,000 free blacks elected to serve the Confederate cause in one capacity or another, some of them even bearing arms. Another 200,000 blacks who were still slaves served the Confederate cause as workers.

There were numerous manifestations of black patriotism for the Confederacy at the outbreak of the war, and as the Northern army marched through the South it was not uncommon for slaves to bury their master’s wealth and their own to try and protect it from the Northerners. As many plantations were left under the supervision of women or the elderly, one would think the situation was ripe for slave rebellions, yet despite this opportunity, and even the efforts of the Union army to incite rebellion, there was not one slave uprising in the South during the entirety of the war.

There were numerous manifestations of black patriotism for the Confederacy at the outbreak of the war, and as the Northern army marched through the South it was not uncommon for slaves to bury their master’s wealth and their own to try and protect it from the Northerners. As many plantations were left under the supervision of women or the elderly, one would think the situation was ripe for slave rebellions, yet despite this opportunity, and even the efforts of the Union army to incite rebellion, there was not one slave uprising in the South during the entirety of the war.

What the author presents is an image of 19th century America that strongly contradicts the myths constructed by the Northern victors of the war. The North, far from being the champion of liberty, was hypocritical both in its treatment of blacks and the abuse of its own impoverished masses. Although Miller does not deny that there were abuses of slavery in the South, he gives a more comprehensive perspective of it that dispels many of the fictions established by abolitionists.

The book itself, like the first of the series, is densely filled with information and examples to demonstrate its points. I imagine that this work may elicit a fair degree of needed debate among historians, and I hope it goes some way towards correcting the historical errors to which we have been subjected.

Continued

From the start he makes a positive Catholic assertion: Every man is a slave, either to sin or the Will of God. Only those who humbly submit themselves to the Divine Will, above their own will, can be truly free. Catholically speaking, humility and obedience are praiseworthy virtues, and there are numerous examples of saints who were slaves during their time here on earth.

Remember that slavery existed both in the Old Testament and at the time of Our Lord and received no condemnation, nor has the Church condemned slavery per se, but rather its abuses. Taking apostolic examples, the author also cites that St. Paul himself urged slaves to obey their masters.

He cites several Popes condemning the abuses of slavery, the slave trade, the unjust enslavement of persons, the separation of slave families and enslavement based on race. Further, slavery is only justified by the Church in conditions where a person is captured in a just war, as punishment for heinous crimes and being born into the state of slavery.

Pope Gregory XVI explicitly condemned the slave trade with the full support of the American Bishops of the South. Creation itself is hierarchical, though Miller stresses that as in all institutions, such as education, employment and marriage, there are instances that transgress the bounds of acceptability. No matter where one seeks there is the taint of fallen human nature.

The good relationship between George Washington & his slaves at Mt. Vernon farm in Virginia reflects well their situation in the South

Espousing ideas condemned by the Church, these men rebelled against the very order of God in their quest for self-governance. Such ideas have contaminated our society today and are in no small part responsible for the robotic repulsion to the idea of human slavery regardless of time or circumstance.

Having analyzed slavery from the Catholic perspective, Miller demonstrates, chapter by chapter, that slavery in America did not start with racism (the first slaves were Catholics and Irish), that the South was not wretched as reported, that the North practiced its own forms of slavery and that Northerners were often much more racially prejudiced than Southerners.

Hypocrisy of the North

The North, historically, had slaves just as the South, though it died out as economically unfeasible. The slave trade brought profits to the North and was perpetuated long after Popes condemned the practice. In the course of a few years Northerners imported far more slaves than were ever freed by such abolitionist movements as “the Underground Railroad.” Ironically, Southern backed legislation intending to end the slave trade was vigorously opposed by the North.

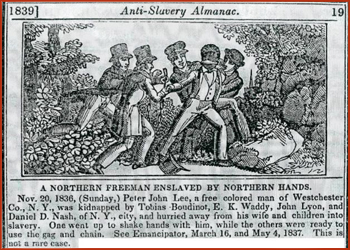

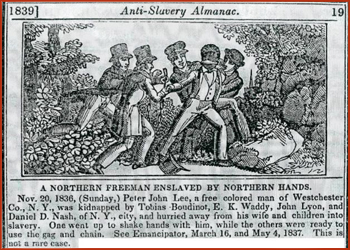

It was not uncommon for a freeman in the North to be taken and re-enslaved

Many Northern States outlawed the black vote as late as 1867. Several imposed laws designed to prevent non-whites from settling. The American Colonization Society, an organization funded by the North, even sought to solve the “problem” of free blacks by sending them to Liberia.

Racism was so fierce that many blacks who had escaped slavery in the South were forced to go on to Canada to flee the race violence of white Northerners. French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville noted during his visit to the U.S that racial prejudice ran deep in the North. There, he said, whites outright refused to work alongside blacks, as was common for workers in the South.

When Lincoln declared the Emancipation Proclamation there was a spike in the desertions in the Northern army, with some officers even submitting their resignation. Many had been told the war was to “preserve the Union,” and riots broke out in several Northern cities to protest a war for liberating blacks. Blacks who fought in the Union army did not even receive the same pay and benefits as their white comrades. Lincoln himself can be frequently found espousing ideas of racial purity and the inferiority of blacks.

Slave of the South, slaves of the North

After exposing the prejudiced treatment of blacks in the North, Miller devotes several chapters to comparing the condition of the average Northern worker with the average Southern slave. In this way the reader gets a more contextual understanding of slavery as it existed in 19th century America and the hardships endured by the working man.

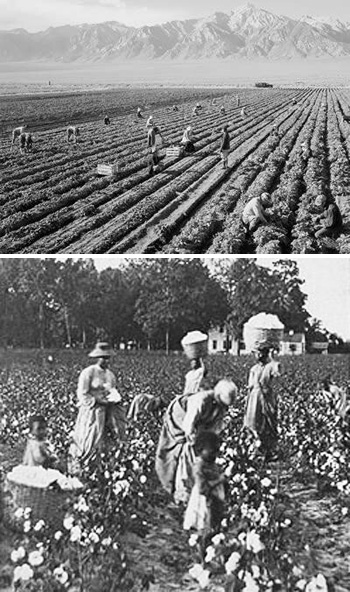

Above, Northern factories where workers had 16 hour days; below, slaves in Southern plantations of rice & cotton (South Carolina) had a more humane labor

The family cell was undermined, as fathers and mothers could be kept away from home for weeks or months at a time, if they weren’t crowded into tenements surrounding the factory complexes. At other times workers were obliged to live in “company towns” where they were provided shacks for housing and were paid in money that was only good at the exorbitantly expensive company store.

The massive industrial system of the North deprived workers of just wages, reduced supposedly free men, women and children (some of whom were literally kidnapped from England and brought to America to work) and discarded those who could no longer turn a profit. It was slavery in all but name.

By contrast Miller examines the condition of the average slave in the South. Contrary to some deeply held myths, many slaves made money, and it was common for slaves to be allotted plots of land where they could grow their own crops for market. In some cases slaves saved up fair amounts of wealth and there were even slaves, as in the case of Simon Phillips, who loaned money to their masters when the owner was in financial distress.

Those who owned few slaves and were not financially well off worked alongside their slaves day in and day out, a practice that was abhorrent to white Northerners. It was also common for slaves to be given training in specialist skills, which would serve them well if they were freed or hired out. In this way a large plantation could resemble a medieval estate, with an amiable and hierarchically ordered self sustaining society.

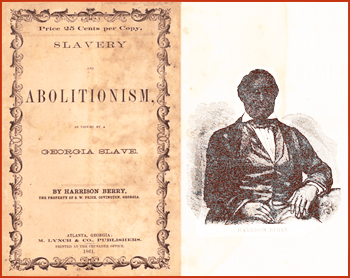

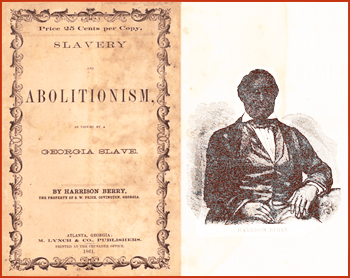

While relations between master and slave were often quite positive, the positions of abolitionists were frequently delusional disingenuous. One slave, Harrison Berry, was so fed up with such Northern distortions that he wrote a book defending slavery and the South. This not only shocked Northerners who believed that slaves were universally miserable, but it destroyed a further myth by showing a slave could write.

This and other works exposed the exaggerations and misrepresentations in such popular, though unrealistic, titles as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Later, the 1930’s slave testimonies, collected by the American government, also show that less than 30% of the interviewees, elderly blacks who still remembered being slaves, had anything negative to say about their masters at all. Some even reported living in better conditions than were available in the ‘30s.

Black confederates

As a final blow to the many racially charged myths surrounding the South, Miller goes on to cite that there were many blacks who actively supported the Southern cause. The numbers in support of this controversial position show that an estimated 60,000 – 93,000 free blacks elected to serve the Confederate cause in one capacity or another, some of them even bearing arms. Another 200,000 blacks who were still slaves served the Confederate cause as workers.

In 1861, slave Harrison Berry wrote a book defending slavery & the South

What the author presents is an image of 19th century America that strongly contradicts the myths constructed by the Northern victors of the war. The North, far from being the champion of liberty, was hypocritical both in its treatment of blacks and the abuse of its own impoverished masses. Although Miller does not deny that there were abuses of slavery in the South, he gives a more comprehensive perspective of it that dispels many of the fictions established by abolitionists.

The book itself, like the first of the series, is densely filled with information and examples to demonstrate its points. I imagine that this work may elicit a fair degree of needed debate among historians, and I hope it goes some way towards correcting the historical errors to which we have been subjected.

Continued

Posted April 15, 2016

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |

Special Edition |