|

Book Reviews

The Da Vinci Code:

Blasphemous Thesis and Bad History

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

Book review of The Da Vinci Code, by Dan Brown

(NY: Doubleday, 2003), 454 pp.

Ordinarily, a serious Catholic would not waste time reviewing a preposterous fiction like The Da Vinci Code. To pay too much attention to the absurd is to give it a credibility it doesn’t deserve. But the book by author Dan Brown, which climbed to the top of the New York Times bestseller list and stayed there, has become a hot topic in numerous Catholic circles.

Many are stunned by the work and asking: What should I say to my friends who believe it? What is true and what is false?

So when John Vennari, editor of Catholic Family News, asked me my views on the novel, I agreed to read it and write a general appraisal.

A blasphemous main thesis

The first thing to say about this book is that a Catholic should reject it emphatically. For its principle thesis is this: Our Lord Jesus Christ was not divine. He was only a man, albeit an extraordinary man. Jesus, from the royal house of David, was married to Mary Magdalene, with the aim of claiming an earthly throne and restoring the line of kings as it was under Solomon. After Christ was crucified, a pregnant Mary Magdalene escaped to France. The seed of Christ that she carried became the root of the Merovingian royal family, and the line, which continues to this day, must be hidden and guarded from enemies, e.g. the male-dominated Catholic Church, which relies on the false history it has created to remain in power.

Only this ensemble of hallucinatory fables should suffice to raise the righteous indignation of the Catholic faithful. But there is more.

According to Dan Brown, Mary Magdalene is the key to understand the mysterious quest for the Holy Grail, or San Greal, which he translates as royal blood, not the sacred chalice of the Last Supper. She was the vessel that bore the royal bloodline of Jesus Christ. The Grail, Brown imagines, is the ancient symbol for womanhood, and the Holy Grail represents the sacred feminine principle. Setting out this feminist ideology, Brown supports the hypothesis championed by Protestants and progressivist scholars who claim the medieval Church “made” Mary Magdalene a prostitute to prevent women from taking their rightful place of power as Christ supposedly intended.

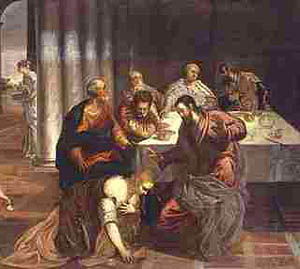

Brown rejects the Catholic tradition of Mary Magdalene the sinner who washes the feet of Jesus, above |

What Jesus really wanted, according to Brown, was an Egalitarian Church headed by Mary Magdalene, a symbol of the “divine feminine principle and goddess.” What does Brown mean by this? I don’t know because he never bothers to explain. He just vaguely implies a notion of some first feminine principle by describing the enemy: the Constantinian Catholic Church that “had subjugated women, banished the goddess, burned nonbelievers, and forbidden pagan reverence for the feminine” (p.239)

Without receiving any historical evidence, the reader is expected to believe a novel and shocking revelation: the history of the Catholic Church has been one long attempt to conceal this bloodline of Mary Magdalene, which has been protected for ages by a secret brotherhood founded in 1099 – the Priory of Sion. The fantastic fable continues. This Priory was the secret society that established the Order of the Knights Templar so that its first nine knights could secretly retrieve ancient documents proving the Christ/Magdalene bloodline hidden under the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The whole ideal of Crusade was just a grand front for the Templars, according to Brown.

It is wholly fabricated. I have read a number of scholarly works on the Knights Templar by authors both pro and con, but I have never seen a drop of evidence that they were founded to protect this “royal” bloodline and venerate the bones of Mary Magdalene. Out of the blue, Brown “reveals” that these relics would be buried beneath the glass pyramid structure at the Louvre. I do not doubt there is an occult significance to the strange pyramid at the Louvre. As for facts, many centuries ago the relics of Mary Magdalene were brought from Aix to Vezelay (France) where a monastery and a basilica were dedicated to her. Innumerable miracles were worked through her intercession, and the site became one of the most famous pilgrimage centers in the Middle Ages. Until today her relics can be venerated by anyone who visits the sanctuary.

A thesis that destroys itself

Besides the blasphemous character of this thesis, unacceptable to Catholics, and its lack of historic basis, to which I will still return, what strikes me is the contradiction that exists within the fable itself.

The author pretends that Mary Magdalene is the feminine principle, the goddess, divine, etc. But, she became divine by the fact that she would have carried the seed of Jesus in her womb. However, Brown denies Christ’s divinity. So, there is a contradiction.

If Christ is not a god, Mary Magdalene isn’t a goddess either.

If she is divine, He has to be divine as well. Then, one would be dealing with two eternal divinities, one masculine and one feminine. It would be an eternal couple, and not an eternal feminine Brown tries to present. Therefore, all the consequences he draws from the first imaginary fact that Magdalene is the goddess suppressed while Christ is mortal are inconsistent and self-destructive.

This is an internal contradiction that in terms of formal logic makes his thesis worth less than a penny.

The history is not factual

The Da Vinci Code is not difficult to refute historically, simply because the data Brown presents in numerous places are not true. To believe Dan Brown’s version of history, one first has to throw out everything recorded in the chronicles and documents of the past. Why? Because they were written by the “winners,” the ones in power, who only write history to serve their hegemonic, privileged, masculine interests. The revisionist history Brown bases his novel on is called postmodern history, which denies the reality of the past except what the historian wants to make of it.

What the reader has, then, is a fiction that claims to be based on historical facts by an author who says that facts and truth do not exist. Only the postmodern man, reduced to a kind of shell of a man with no sense of an absolute truth and reality, would put any faith in this spoof of a spoof.

One of Brown’s many foolish contentions is that Constantine called the Council of Nicea in 325 to transform Jesus Christ from a “mere mortal” to the “Son of God” (pp. 232-4). The blood of the martyrs in the Coliseum stands as proof that the early Christians were prepared to die rather than deny the divinity of Jesus Christ. Long before the Council of Nicea, early Church Fathers such as St. Ignatius of Antioch, St. Irenaeus, St. Cyprian of Carthage, and others clearly preached the divinity of Christ. Consider these words of St. Clement of Alexandria written in 190 AD: “Christ alone is both God and man, and the source of all our good things” (Exhortation to the Greeks 1:7:1).

As for the Council of Nicea, it was convoked by the Emperor, but the direction of the sessions was left to the some 250 Bishops who assembled to debate the claims of Arius. This heretic sustained that while Christ was divine, he was less than the Father. The vote against Arius was hardly “relatively close,” as Brown asserts (p. 232). Only two Bishops supported the heretic. These are the historical facts, quite different from the fabrications Brown uses as base for his novel.

Brown bases his claims for the marriage of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene and an egalitarian church on the Gnostic Gospels (p. 231), apocryphal texts written some 50-75 years after the Gospels of the Canon. Christianity, according to Brown, is a corruption of the Gnostic church that worshipped the divine feminine. He presents “gnosis” as if it were a single defined sect with a unified doctrine, like Christianity. This is an erroneous representation of gnosis and biblical history.

First, gnosis is a collective name for a large number of greatly varying pantheistic sects, which flourished from some time before Christ, revived in the 3rd century, and continued into our times. Basically, the Gnostics held matter to be a deterioration of spirit, and the whole universe a degradation of the deity. The Gnostic origin of the world appears in concise form in its Gospel of Philip: “The world came into being through a transgression.” It taught the ultimate end of all being was to overcome the grossness of matter and return to a Parent-Spirit. Some of its many sects have a “Mother” or a “sophia” as the divine feminine, but others do not. So, Brown’s generalization that gnosis – all sects included – have the divine feminine principle is not objective.

Second, biblical scholars uniformly agree that the Gnostic gospels are apocryphal texts that never reflected the beliefs of the followers of Christ. Even a feminist theologian like Sr. Elizabeth Johnson, professor at Fordham University, admits that no historical credence can be given to the Gnostic gospels or a supposed marriage of Christ and Mary Magdalene. (1)

Nor did Constantine commission a new Bible, picking and choosing what pleased him, as Brown claims (p. 234). The four Gospels of the Bible had established themselves as authentic by the end of the 2nd century, as attested by Church Fathers. (2) Brown’s history is fiction.

Old myths repeated

The Da Vinci Code repeats some tired old myths that today’s historians have discarded as propaganda or lies. To feed the fire of his supposedly anti-woman Catholic Church theory, Brown says the Catholics in the Middle Ages burned seven million witches (p. 125). In fact, the most recent studies show that during the period 1400-1700 an estimated 40,000 persons were executed as witches, many of them by Protestants. In the Middle Ages, relatively few witches were condemned. (3)

According to Brown, the Knights Templars would have been a front for an imaginary secret society, the Priory of Sion |

No serious historian has found any record of the strange secret beginnings mentioned above that Brown claims for the Knights Templar, which became a prototype for crusading orders. He also credits the Templars with inventing Gothic architecture, adopting occult symbols, and adoring pagan gods. Finally, Brown continues, they were destroyed by a sting operation masterminded by Pope Clement V, who burned “hundreds of Templars” and tossed their ashes into the Tiber (p. 338). Then the order went underground and mutated into the Templar orders in Freemasonry today.

The charges are either fabricated or grossly exaggerated. There is no evidence that the medieval Templars were master architects or artists; they were soldier-knights whose first concern was battle and defending the Holy Land. It was King Philippe IV of France, and not the puppet Avignon Pope, who conspired against the Templars and spread charges of heresy and magical practices. It was also under the influence of this King that cruel torture was exercised to elicit confessions, which were later retracted.

The vast literature on the Templars has been synthesized for English readers in recent scholarly works that have concluded that no convincing physical evidence of heresy was ever found. (4) Notwithstanding, Philippe the Fair forced the issue with the irresolute Pope and insisted on their suppression.

As far as the Pope throwing the ashes of hundreds of burned Templars into the Tiber, no record exists of any Templar burned in Rome or in any other Italian city on the Tiber’s banks. Less than a hundred were burned in Paris and several other French cities. Nor, as he claims, was the first residence of the Knights Templar in the “old stables” under the Temple of Solomon. They lived in a wing of the royal palace on Temple Mount, next to the Al-Aqsa mosque.

How can anyone put credence in Brown’s historical conjectures when his facts are just plain wrong? He is writing fiction, pure and simple.

Disputable assertions about secret societies

Brown interweaves his book with shocking and little-known information about the symbols and rites of the Rosicrucians, Freemasonry, and secret societies. Some is true; a lot is false; the result, a grand mishmash of revelations and conspiracies intended to titillate the public and sell books. For example, he describes pagan sexual orgies like the Hieros Gamos, which in fact, according to reputed authors, existed and still exist to this day in the secret societies.

Further, the historical personages that the author pretends were listed on a “secret dossier” of grand masters of the Priory of Sion (pp. 326-7) are known to be linked to various occult groups, not a single entity.(5) Isaac Newton, for example, was part of the “invisible College” that met at Oxford; Alexander Pope was enrolled in the ranks of Freemasonry, and Victor Hugo was steeped in esoterica and the legends of the sacred feminine. But according to Brown’s fantastic invention, they all would be leaders of his fictitious Priory of Sion.

Some of Leonardo da Vinci's paintings, like the John the Baptist above, have occult notes. The adrogynous look of this feminine man seems similar to the somewhat masculine appearance of the Mona Lisa, below

|

What about Leonardo da Vinci, who Brown says “knew the secret” (the Magdalene bloodline) and encoded his paintings with images of the sacred feminine? The novel proposes that in Leonardo’s Last Supper, the figure at Christ’s right, held to be St. John, is really Mary Magdalene, and the “V” space between the two is a symbol of the sacred feminine. Any truth to this?

The figure of Leonardo da Vinci, about whom so much has been written, has been reputed a homosexual and dabbler in alchemy and necromancy.(6) He was a follower of Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola and other Renaissance Humanists who were rediscovering the pantheist and Gnostic doctrines of the ancients. I have heard art lectures demonstrating how many of the Renaissance court painters, including Leonardo da Vinci, encoded doctrines of gnosis in their paintings. (7) But it is beyond the pale to propose that Leonardo would have imagined Mary Magdalene to be present as St. John at the Last Supper.

There is a known rule of apologetics that states: “Quod gratis asseritur, gratis negatur” – those things that are freely affirmed, can be freely denied.” Since no evidence was presented by the author about this extravagant substitution – St. John would be St. Mary Magdalene – everyone has the right to staunchly deny it.

I think the deeper intent of Brown’s presentation of the symbols and secrets of Freemasonry, Kaballah, etc is to try to make these occult societies appear as a single, united reality. This supposed unity would give prestige to his imaginary league. The reality however, is different. These forces of evil only unite themselves when they join to fight against the Catholic Church and Christendom. Otherwise, they brawl among themselves like demons. The internal quarreling among Protestants is an above-ground example of what happens in the secret societies.

At any rate, Brown tries to charm the reader with his lies in order to give the impression that the ensemble of secret societies is good. In parallel he always presents the Catholic Church as bad.

Is the revolutionary modern man prepared to accept the good as bad, and the bad as good? Is he finally ready to reject the divinity of Christ? That is the more profound proposal The Da Vinci Code brings to light of day.

Conclusion

It is my opinion that The Da Vinci Code was intended principally to shock a novelty-craving public and destroy the stability of the Catholic Faith. This is why the trumpets of liberal propaganda are sounding to promote it.

Given its lack of seriousness and historical objectivity, this book should be rejected as an irrelevant inanity. Given its blasphemous character, it should raise general indignation.

I hope this review will contribute to such good reactions.

1. Elizabeth Johnson, “Cracking the Da Vinci Code,” St. Anthony Messenger, July 2004

2. Carl Olson and Sandra Miesel, The Da Vinci Hoax (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2004), pp. 65-6.

3. Jenny Gibbons, “Recent Developments in the Study of The Great European Witch Hunt,” #5, Pomegranate (Lammas, 1998).

4. Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars, (Cambridge University Press: 1978); Edward Burman, The Templars Knights of God, (Rochester, VA: Destiny Books, 1986); Peter Partner, The Murdered Magicians: The Templars and Their Myth (Oxford: OUP, 1982).

5. Robert Richardson, The Unknown Treasure: The Priory of Sion Fraud and the Spiritual Treasure of Rennes-le-Château (Houston, TX: NorthStar, 1998). A summary of the work, “The Priory of Sion Hoax,” can be read on Alpheus.com website.

6. A. Richard Turner, Inventing Leonardo (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), p. 13; Roger Whiting, Leonardo: A Portrait of the Renaissance Man (NY, Knickerbocker Press, 1998), p. 18.7. Turner gives an extensive history of the critical interpretations of the works of Leonardo, extending from Vasari’s biography in the 16th century to the commentary of William Butler Yeats in the 20th century. Inventing Leonardo, pp.100-52

Posted on September 8, 2004

|

Book Reviews | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|