The Best of...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

of the Social Reign of Christ

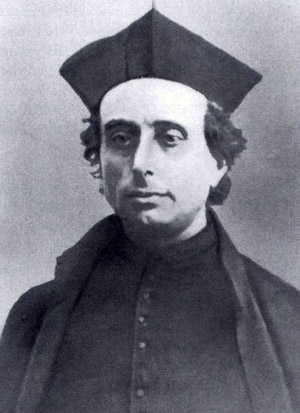

Fr. Henri Ramière

The French Jesuit Fr. Henri Ramière (1821-1884) was a renowned theologian, philosopher, historian, writer and great apostle of the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus; he founded a monthly magazine Messenger of the Heart of Jesus and edited it until the end of his life.

At Vatican Council I, he was a strong opponent of the Liberalism he saw entering the Church and society. Pope Pius IX congratulated this Jesuit for his work titled Church Teaching on Liberalism (Les Doctrines Romaines sur le Libéralisme). In 1871 the same Pope entrusted him with the task of writing to all the Catholic Bishops commanding them to promote the consecration of the Christian world to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

To demonstrate how the tenets of Liberalism that Fr. Ramière warned against have become common thinking among Catholics, today under the title of Progressivism, TIA transcribes here a very opportune chapter of his outstanding work, The Social Reign of the Heart of Jesus (Le Règne Social du Coeur de Jesus), published in Toulouse, France.

This chapter was also published twice as an article in his monthly Messenger in September 1868 and in 1871 under the title "Dangers of Catholic Liberalism."

In the world there was an army whose history, through 18 centuries, was an uninterrupted series of apparent reverses and real triumphs. Always fighting against enemies a hundred times more numerous, this army had conquered them all, and its flatterers assured it that it had annihilated them. Guard of a citadel of which God was the protector, it laughed at the assaults of the mighty on earth; and the futility of the efforts of the greatest conquerors to weaken it gave it the right to despise the future attacks it would face.

But, behold, the enemy, unable to overcome this army by force, resorted to an infernal stratagem: He addressed himself to the defenders of the citadel and entrusted to them the charge of demolishing the fortifications and opening the gates. However, in order to gain their consent, he did not foolishly propose to them such a betrayal, which the loyal spirits of that army’s warriors would have rejected.

The enemy’s craft had more skill: He appealed to the warriors' generosity; he persuaded them that if they had the right to defend the citadel, their adversaries had an equal right to attack it. Therefore, justice required that, instead of expending all their forces to reject these attacks, they should defend the rights of the assailants.

The maneuver, unfortunately, had an effect: Inside that powerful army, which unity had made invincible, a numerous party formed that took as a war cry "the freedom to attack!" Those who did not want to enlist in this party found themselves, on the part of their brothers-in-arms, the target of a hostility more acerbic than that of the enemies. This hostility extended even to the Chief chosen by God to command this army. His own soldiers – regardless of the firmness that had maintained a strict discipline in the army, which until that day had been its strength – did not fear to contest the prerogative of his supreme authority.

There is not one of our readers who has not seen through the transparent veil of this allegory and applied it to the dangers to which Liberalism exposes the army of Jesus Christ. This is, in truth, the weeds sown by the enemy in the field of the head of a household. It is the trap by which so many noble hearts allowed themselves to be caught. It is the strategy that gave advantages to the immortal Adversary of Truth that violence did not give.

*

What, then, is Catholic Liberalism? It is a mitigated form of absolute Liberalism, or, in other words, free-thinking. It has always been the tactic of the Father of Lies to unite more moderate errors with extreme errors, thus to more readily seduce those who would be repelled by absolute denials of the Faith.

This is how in the 17th and 18th centuries Jansenism, a mitigated Lutheranism, dragged along many minds that would have repelled Luther's blasphemy. The free-thinkers are the Protestants of the 19th century and the legitimate descendants of Luther.

Luther protested against the supremacy of the Pope and against the authority of the Church; free-thinkers protest against the authority of Jesus Christ and the supremacy of truth. Luther claimed for every "Christian" the right to believe and teach what he thought he had found in the Bible; free-thinkers claim for every man the right to think and to maintain everything his reason invents.

The Protestants did not want any fixed dogma in the supernatural order; free-thinkers do not want any fixed principle in the rational order. In their view, there are only opinions and the public power has no right over these opinions; rather people should be given ever greater freedom to present and spread their personal opinions.

If someone wants to attack the existence of God, the soul, the future life and the most essential laws of morals, civil law should have no say in the matter. There is no crime to hold an opinion and, since thought is free, the word and the press must be equally so. Such is absolute Liberalism, which is also called Rationalism, the great dogmatic heresy of the 19th century.

Catholic Liberalism is far from reaching this point. It does not make the monstrous concessions to error that would destroy the integrity of the Faith. It does not deny that there is an absolute truth to which man must give the assent of his reason; it does not dispute the divinity of Jesus Christ and the authority of the Church; rather, it concurs with free-thinking in enclosing the faith in those truths that lie in the sphere of the individual conscience.

According to Catholic LIberalism with regard to society and the power that governs it, truth has no more rights than error. The public power should view those who hold both as merely having opinions whose freedom it is obliged to protect – as long as they do not resort to violence in order to obstruct the freedom of opposing opinions.

Thus, in the eyes of liberals, be they Catholic or anti-Catholic, the law must be atheistic, that is, it should not be concerned about God, as if He did not exist. For them, His precepts are non-existent, His authority is null and void, His Revelation worthless. In his intimate circles, as a Catholic and as a man, the magistrate can believe all this, but as a magistrate, in the exercise of his authority, he must behave absolutely as if he does not believe in anything.

The liberal theory requires, therefore, for all Catholics engaged in public office to have two consciences: a personal conscience, according to which all his personal actions conform to the law of God and a public conscience, which allows him to ignore any of these laws in the performance of his functions. As a Catholic, he hears Mass, and as a magistrate he assists at the laying of the cornerstone of a mosque. If we were still living in the time of Paganism, he would accompany Caesar to the temple of the idols.

We do not affirm that all Catholic liberals admit this theory in its full extension. To the contrary, we know that many refuse to bring to term the consequences of such principles; nonetheless, the consequence follows no less logically from the principles.

In fact, there is no middle ground: Either society is subject to God and then is obliged to defend His rights and to conform to His precepts, as Catholic doctrine prescribes; or society is independent of God and then has the absolute right not to be concerned about Him, which is legal Atheism.

The application of the two theories can suffer various modifications, but one theory absolutely excludes the other, and we must choose between them. If we defend, at least in theory, the supremacy of truth, we are Catholics; if we concede to error the same rights as truth, we are liberals.

For the anti-Catholic Liberalism this equality between truth and error is absolute; for the Catholic Liberalism it relates only to society and to the power that governs it. These are two different errors, but they agree in denying the rights of truth. In fact, even though this second form of Liberalism is much less repugnant than the first, it is no less opposed to Catholic doctrine and we do not exaggerate by qualifying it as heresy. For it is evident that it denies at the same time the rights of God, of Jesus Christ and of the Church.

Either God is nothing or He is the Sovereign Lord of all of societies as well as of individuals. To want to place Him outside of the law, to deny Him the essential authority, is to deny Him existence. Legislative Atheism necessarily leads to doctrinal Atheism.

Jesus Christ, no less than God His Father, has the right to the homage and the obedience of societies. When Christ came to earth, the Eternal Father gave to Him not only souls, but also the nations. He made Him Sovereign King and the only Savior of both peoples and individuals, applying the word of the Apostle: "For there is no other name under heaven given to men, whereby we must be saved." (Acts 4:12)

By thus authorizing peoples to disregard the teachings and precepts of Jesus Christ in their collective existence, Liberalism violates the rights of the Heavenly Father as well as those of His Only Begotten Son.

In the same way Liberalism attacks the authority of the Church. In fact, she was made the sovereign depository of the Incarnate Word and the supreme interpreter of His law. Our Lord told the Apostles, "Go, therefore, and teach all nations, teaching them to observe all the things that I have commanded you." (Mt 28:19-20)

Here He makes no distinction between social and individual duties. He did not say to the Apostles, "Go and teach every man what he personally owes to God, but do not be concerned about what men assembled in a society owe to one another." He speaks not only to individuals, but to nations. When, therefore, Liberalism removes societies from the authority of the Church, leaving them to answer only to their individual consciences, with one stroke it reduces to nothing the institution of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the mission of the Church.

Yes, it reduces both to nothing, because the truth is one and indivisible. To want to divide truth into two parts, and then sacrifice one to the demands of the world in order to better maintain the other, is to destroy it entirely. We can be disposed to make excuses for the intentions of the Catholics who make this calculation, imagining that we are rendering a great service to the truth, but we are obliged to clearly tell them, with the Pope, that such a service rendered to the truth by its defenders is more harmful to it than the violent attacks of its enemies.

It is the judgment of Solomon – who ordered the baby of two women, who both claimed him, to be cut in half – applied in reverse, not on a mortal child, but on the immortal truth. The division, which for Solomon was just a sham, would ask liberal Catholics to do what is manifestly impossible. A man placed between his conscience, which is Catholic, and public opinion, which no longer is, and tries to save both cannot do so. To take up the sword and strike is to try to cut the truth into two pieces.

To public opinion he surrenders the social rights of this divine truth even as he preciously guards his individual rights for himself. How can he not see that the divine truth thus mutilated is no longer the truth and no longer has anything of the divine? If God no longer governs social relations, then He obviously does not deserve the homage of individuals. Ceding this point to free-thought, he thus surrenders it all; he hands over the citadel and sacrifices the crown of the Divine King, who he boasts to defend.

"But," as liberal Catholics say, "if we refuse this satisfaction to public opinion, it becomes irritated by us and we are unable to exert any influence over it."

Yes, this is true. Just as the Christians of the first centuries could not confess the unity of God and the divinity of Jesus Christ without raising the public opinion of their time against them, so also we cannot. It is always the same fight although the terrain is different. It is the secular battle against Jesus Christ.

To pretend to facilitate the salvation of the world by sacrificing the rights of the Savior would be to deceive ourselves with a foolish hope. Doing this, we would only make salvation impossible: first, because Jesus Christ would no longer be the true Savior if He were not the necessary Savior; second, because instead of conquering the affection of the world, we would only procure its contempt; third, because the truth would cease to have the power to save men should its defenders cease to assert it in all its integrity.

Indeed, it is not the attacks of the enemies that weaken the truth; these attacks, on the contrary, make it shine even brighter. Its very nature is to be combated by error, just as it is the nature of light to be opposed to darkness. So long as the truth is boldly, courageously and wholly asserted by those whom it chose to be its organs on earth, it retains all its power to enlighten minds of good faith.

But, if the organs charged with manifesting it to the world affirm it only half-way, how can obscure minds know it? What profit will error not draw in the fight from the imprudent concessions of its defenders?

Without a doubt, these mitigated errors, which seduce Catholics and even priests, are incomparably more disastrous to the truth than the extreme errors professed only by those who are openly impious. If the lamp that lights the house is hidden under the bushel, how can its inhabitants not stumble in the darkness? If the salt becomes tasteless, what is left to preserve the world from corruption?

Therefore, Pius IX did not exaggerate when he denounced Liberalism as a scourge more frightful to Catholic France than the violence of the tyrants of the Commune [the radically communist government that ruled Paris from March 19 to May 28, 1871). In so doing, he was not comparing the liberal Catholics to the leaders of the Commune. Rather, he likened the results of the illusion of the former to the consequences of the tyranny of the latter.

Fr. Henri Ramière (1821-1884) |

To demonstrate how the tenets of Liberalism that Fr. Ramière warned against have become common thinking among Catholics, today under the title of Progressivism, TIA transcribes here a very opportune chapter of his outstanding work, The Social Reign of the Heart of Jesus (Le Règne Social du Coeur de Jesus), published in Toulouse, France.

This chapter was also published twice as an article in his monthly Messenger in September 1868 and in 1871 under the title "Dangers of Catholic Liberalism."

In the world there was an army whose history, through 18 centuries, was an uninterrupted series of apparent reverses and real triumphs. Always fighting against enemies a hundred times more numerous, this army had conquered them all, and its flatterers assured it that it had annihilated them. Guard of a citadel of which God was the protector, it laughed at the assaults of the mighty on earth; and the futility of the efforts of the greatest conquerors to weaken it gave it the right to despise the future attacks it would face.

But, behold, the enemy, unable to overcome this army by force, resorted to an infernal stratagem: He addressed himself to the defenders of the citadel and entrusted to them the charge of demolishing the fortifications and opening the gates. However, in order to gain their consent, he did not foolishly propose to them such a betrayal, which the loyal spirits of that army’s warriors would have rejected.

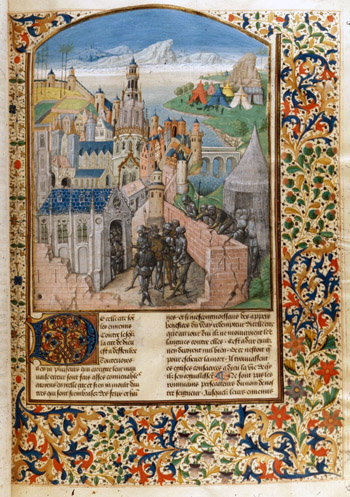

A citadel that for centuries triumphed over all the assaults of the enemy |

The maneuver, unfortunately, had an effect: Inside that powerful army, which unity had made invincible, a numerous party formed that took as a war cry "the freedom to attack!" Those who did not want to enlist in this party found themselves, on the part of their brothers-in-arms, the target of a hostility more acerbic than that of the enemies. This hostility extended even to the Chief chosen by God to command this army. His own soldiers – regardless of the firmness that had maintained a strict discipline in the army, which until that day had been its strength – did not fear to contest the prerogative of his supreme authority.

There is not one of our readers who has not seen through the transparent veil of this allegory and applied it to the dangers to which Liberalism exposes the army of Jesus Christ. This is, in truth, the weeds sown by the enemy in the field of the head of a household. It is the trap by which so many noble hearts allowed themselves to be caught. It is the strategy that gave advantages to the immortal Adversary of Truth that violence did not give.

What, then, is Catholic Liberalism? It is a mitigated form of absolute Liberalism, or, in other words, free-thinking. It has always been the tactic of the Father of Lies to unite more moderate errors with extreme errors, thus to more readily seduce those who would be repelled by absolute denials of the Faith.

This is how in the 17th and 18th centuries Jansenism, a mitigated Lutheranism, dragged along many minds that would have repelled Luther's blasphemy. The free-thinkers are the Protestants of the 19th century and the legitimate descendants of Luther.

The circle of so-called 'reformers' with Luther at the center who challenged the supremacy of truth |

The Protestants did not want any fixed dogma in the supernatural order; free-thinkers do not want any fixed principle in the rational order. In their view, there are only opinions and the public power has no right over these opinions; rather people should be given ever greater freedom to present and spread their personal opinions.

If someone wants to attack the existence of God, the soul, the future life and the most essential laws of morals, civil law should have no say in the matter. There is no crime to hold an opinion and, since thought is free, the word and the press must be equally so. Such is absolute Liberalism, which is also called Rationalism, the great dogmatic heresy of the 19th century.

Catholic Liberalism is far from reaching this point. It does not make the monstrous concessions to error that would destroy the integrity of the Faith. It does not deny that there is an absolute truth to which man must give the assent of his reason; it does not dispute the divinity of Jesus Christ and the authority of the Church; rather, it concurs with free-thinking in enclosing the faith in those truths that lie in the sphere of the individual conscience.

According to Catholic LIberalism with regard to society and the power that governs it, truth has no more rights than error. The public power should view those who hold both as merely having opinions whose freedom it is obliged to protect – as long as they do not resort to violence in order to obstruct the freedom of opposing opinions.

Thus, in the eyes of liberals, be they Catholic or anti-Catholic, the law must be atheistic, that is, it should not be concerned about God, as if He did not exist. For them, His precepts are non-existent, His authority is null and void, His Revelation worthless. In his intimate circles, as a Catholic and as a man, the magistrate can believe all this, but as a magistrate, in the exercise of his authority, he must behave absolutely as if he does not believe in anything.

John Kennedy won only after he assured the people he supported absolute separation of Church and State |

We do not affirm that all Catholic liberals admit this theory in its full extension. To the contrary, we know that many refuse to bring to term the consequences of such principles; nonetheless, the consequence follows no less logically from the principles.

In fact, there is no middle ground: Either society is subject to God and then is obliged to defend His rights and to conform to His precepts, as Catholic doctrine prescribes; or society is independent of God and then has the absolute right not to be concerned about Him, which is legal Atheism.

The application of the two theories can suffer various modifications, but one theory absolutely excludes the other, and we must choose between them. If we defend, at least in theory, the supremacy of truth, we are Catholics; if we concede to error the same rights as truth, we are liberals.

For the anti-Catholic Liberalism this equality between truth and error is absolute; for the Catholic Liberalism it relates only to society and to the power that governs it. These are two different errors, but they agree in denying the rights of truth. In fact, even though this second form of Liberalism is much less repugnant than the first, it is no less opposed to Catholic doctrine and we do not exaggerate by qualifying it as heresy. For it is evident that it denies at the same time the rights of God, of Jesus Christ and of the Church.

Either God is nothing or He is the Sovereign Lord of all of societies as well as of individuals. To want to place Him outside of the law, to deny Him the essential authority, is to deny Him existence. Legislative Atheism necessarily leads to doctrinal Atheism.

Jesus Christ, no less than God His Father, has the right to the homage and the obedience of societies. When Christ came to earth, the Eternal Father gave to Him not only souls, but also the nations. He made Him Sovereign King and the only Savior of both peoples and individuals, applying the word of the Apostle: "For there is no other name under heaven given to men, whereby we must be saved." (Acts 4:12)

The truth of Christ must reign in both the temporal and religious spheres |

In the same way Liberalism attacks the authority of the Church. In fact, she was made the sovereign depository of the Incarnate Word and the supreme interpreter of His law. Our Lord told the Apostles, "Go, therefore, and teach all nations, teaching them to observe all the things that I have commanded you." (Mt 28:19-20)

Here He makes no distinction between social and individual duties. He did not say to the Apostles, "Go and teach every man what he personally owes to God, but do not be concerned about what men assembled in a society owe to one another." He speaks not only to individuals, but to nations. When, therefore, Liberalism removes societies from the authority of the Church, leaving them to answer only to their individual consciences, with one stroke it reduces to nothing the institution of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the mission of the Church.

Yes, it reduces both to nothing, because the truth is one and indivisible. To want to divide truth into two parts, and then sacrifice one to the demands of the world in order to better maintain the other, is to destroy it entirely. We can be disposed to make excuses for the intentions of the Catholics who make this calculation, imagining that we are rendering a great service to the truth, but we are obliged to clearly tell them, with the Pope, that such a service rendered to the truth by its defenders is more harmful to it than the violent attacks of its enemies.

It is the judgment of Solomon – who ordered the baby of two women, who both claimed him, to be cut in half – applied in reverse, not on a mortal child, but on the immortal truth. The division, which for Solomon was just a sham, would ask liberal Catholics to do what is manifestly impossible. A man placed between his conscience, which is Catholic, and public opinion, which no longer is, and tries to save both cannot do so. To take up the sword and strike is to try to cut the truth into two pieces.

To public opinion he surrenders the social rights of this divine truth even as he preciously guards his individual rights for himself. How can he not see that the divine truth thus mutilated is no longer the truth and no longer has anything of the divine? If God no longer governs social relations, then He obviously does not deserve the homage of individuals. Ceding this point to free-thought, he thus surrenders it all; he hands over the citadel and sacrifices the crown of the Divine King, who he boasts to defend.

"But," as liberal Catholics say, "if we refuse this satisfaction to public opinion, it becomes irritated by us and we are unable to exert any influence over it."

Yes, this is true. Just as the Christians of the first centuries could not confess the unity of God and the divinity of Jesus Christ without raising the public opinion of their time against them, so also we cannot. It is always the same fight although the terrain is different. It is the secular battle against Jesus Christ.

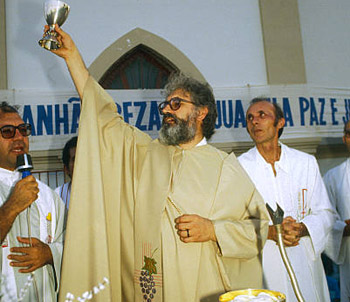

The execution of priests by liberals at the Paris Commune was less effective than Progressivism's infiltration in the Church, below, Fr. Boff leader of Liberation Theology |

|

Indeed, it is not the attacks of the enemies that weaken the truth; these attacks, on the contrary, make it shine even brighter. Its very nature is to be combated by error, just as it is the nature of light to be opposed to darkness. So long as the truth is boldly, courageously and wholly asserted by those whom it chose to be its organs on earth, it retains all its power to enlighten minds of good faith.

But, if the organs charged with manifesting it to the world affirm it only half-way, how can obscure minds know it? What profit will error not draw in the fight from the imprudent concessions of its defenders?

Without a doubt, these mitigated errors, which seduce Catholics and even priests, are incomparably more disastrous to the truth than the extreme errors professed only by those who are openly impious. If the lamp that lights the house is hidden under the bushel, how can its inhabitants not stumble in the darkness? If the salt becomes tasteless, what is left to preserve the world from corruption?

Therefore, Pius IX did not exaggerate when he denounced Liberalism as a scourge more frightful to Catholic France than the violence of the tyrants of the Commune [the radically communist government that ruled Paris from March 19 to May 28, 1871). In so doing, he was not comparing the liberal Catholics to the leaders of the Commune. Rather, he likened the results of the illusion of the former to the consequences of the tyranny of the latter.

Fr. Henri Ramière, Le Règne Social du Coeur de Jesus,

Toulouse, France, 1832, chapter "Dangers of Catholic Liberalism"

Posted July 23, 2018

Toulouse, France, 1832, chapter "Dangers of Catholic Liberalism"

Posted July 23, 2018

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |