Organic Society

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contracts & Honor - III

The Importance of the Inauguration Oath

One of the interesting manifestations of the importance of an oath was the role it played in the inauguration of a Head of State.

In principle the Head of State could not take possession of his office until he had taken an oath promising to fulfill his obligations.

Today it has become an empty solemnity. The inauguration ceremony is a pretext to party and drink champagne. Very few people believe that the oaths of the Presidents of our Republics represent any substantial change to their pre-established agendas. Anyone who imagines that the political and social order of his country became much stronger because a president took his oath runs a serious risk of being considered naïve. In our days neither the ones who take the oath nor those who hear it grant any substantial importance to it.

In the Middle Ages the situation was completely different. The oath played such a sacred role that, in a certain way, it was the respect for the oath that destroyed the Holy German Roman Empire.

In the Middle Ages the situation was completely different. The oath played such a sacred role that, in a certain way, it was the respect for the oath that destroyed the Holy German Roman Empire.

The formula of the imperial oath was variable. Each new Emperor had to commit to something more than the previous one in a ceremony called capitulation. Each Emperor had to give more guarantees that he would not limit the various liberties of his subjects. Thus, the oath of the Emperor became increasingly long and his power increasingly smaller.

In this way his subjects acquired so many rights that the Emperor became primarily a symbol. He was bound by that solemn oath and could do very little practically speaking, while his subjects became excessively independent. This process practically destroyed the Holy Empire. But no one even considered that the Emperor should violate his oath in order to increase his power. This shows the value placed on a man’s word of honor in taking an oath.

Oath of the Emperor before the Pope

Before it reached this exaggerated situation, each Emperor - either before or after his coronation - had to be crowned Rex Romanorum, King of the Romans, by the Pope or his representative. For this purpose he had to take an oath promising he would protect the Church in different ways.

The Pope or his representative would put questions to the candidate: “Will you defend the Holy Faith? Will you defend the Holy Church? Will you defend the kingdom? Will you maintain the temporal laws? Will you maintain justice? Will you show due submission to the Pope?” To each of these he responded, “I will.” The Emperor-to-be then would lay two fingers on the altar and swore his oath.

For us to understand the importance of this coronation, we have to consider that while the Church had her Papal Territories, she did not have a proportionately strong army to protect them. She relied, therefore, on the military assistance of the Emperor, who would send his troops to protect the territories if a temporal lord invaded them or oppressed the Pope.

Thus, the Pope had a special interest in crowning the future Emperor as King of the Romans. As part of the agreement, the Church agreed to pay the expenses of the imperial troops she requested. Curiously, she also would cover the expenses for the future Emperor’s trip to Rome to be crowned.

For the Emperor this ceremony was also quite significant. When Charlemagne was crowned Emperor in 800 by Pope Leo III, both considered that the new Empire instituted was a continuation of the Western Roman Empire, which had ended in the 5th century. So, the title of King of the Romans was in some ways a continuation of the rule of those previous Roman Emperors over the Roman people. Further, given the pivotal importance of the Church in the Middle Ages, no King could maintain himself on his throne without having been officially crowned by the Church.

For the Emperor this ceremony was also quite significant. When Charlemagne was crowned Emperor in 800 by Pope Leo III, both considered that the new Empire instituted was a continuation of the Western Roman Empire, which had ended in the 5th century. So, the title of King of the Romans was in some ways a continuation of the rule of those previous Roman Emperors over the Roman people. Further, given the pivotal importance of the Church in the Middle Ages, no King could maintain himself on his throne without having been officially crowned by the Church.

As an example of the medieval oath, we have the one taken by the future Emperor Otto IV on July 12, 1198, in Aachen during the ceremony where he was crowned King of the Romans. He promised to the Archbishop of Cologne representing Pope Innocent III to protect all the rights of the Church, conserve and defend all her possessions, and help her retake from usurpers the territories she had lost. He also promised obedience to the Pope and his successors and pledged to follow the counsel and will of the Pope to maintain the good customs of the Roman people.

Shortly afterward, a delegate of the Pope delivered to Otto IV in Cologne a written papal document recognizing him “by the grace of God and the Pope” as King of the Romans. In this document the Pope threatened excommunication to anyone who violated the fulfillment of the King’s oath. This applied not only to those who would oppose the Emperor from carrying out his promises, but also to the Emperor himself, should he would break his oath.

Punishing in a dishonoring way

The seriousness given to promises was a consequence of the central role played by honor in society. The high importance of honor explains the rigor taken against those who committed crimes of dishonor. The Middle Ages with its profound juridical sense had many offenses it qualified as crimes against honor. Those were punished with penalties that touched upon the honor of the criminal, as well.

We know that some crimes against the virtue of purity were severely punished in some cities of Germany. The guilty party, escorted by public officials, had to walk through the city exposed to the people’s scorn for his crime. At times he was obliged to wear a pig’s head over his own, a symbol of his dirty actions. A herald who accompanied the tour would stop and read the verdict against him in the public squares of the city. Boys would follow the procession making fun of him and throwing vegetables or eggs at him.

We know that some crimes against the virtue of purity were severely punished in some cities of Germany. The guilty party, escorted by public officials, had to walk through the city exposed to the people’s scorn for his crime. At times he was obliged to wear a pig’s head over his own, a symbol of his dirty actions. A herald who accompanied the tour would stop and read the verdict against him in the public squares of the city. Boys would follow the procession making fun of him and throwing vegetables or eggs at him.

Often after such a punishment, the person was obliged to move away from that city. This was a punishment turned toward maintaining virtue and honor in society.

Other medieval cities often had a column or a pillory in a main square to which a criminal was tied facing the public. A written verdict of his crime was tacked to the pillar above his head. Thus, any person walking by could approach the pillory, read about his crime and manifest his disapproval to the criminal.

Other times it was a Pope or a King who would rigorously punish a vassal who broke his oath of fidelity. For example, Boniface VIII, who was a great Pope, had members of the Colonna family as temporal vassals. The latter revolted against him, and, as a consequence, the Pope called his faithful vassals to march against the Colonnas. The Pope’s troops went to Palestrina, one of the Colonnas’ headquarters, and razed the city to the ground.

For some of us this punishment would appear too violent. It is because we have lost the notion of honor and the horror of breaking a promise to one’s superior. We no longer comprehend the villainy of a feudal lord who would revolt against his suzerain. To restore our lost sense of honor, we would benefit from meditating on the dishonor of Judas’ treason.

It is very easy to say that Boniface VIII should have shown charity when we have lost the moral sense and do not understand the enormity of the crime of revolt, especially a revolt against the Pope.

It was this atmosphere of honor that caused the Pope to be the most respected and esteemed man in all Christendom, precisely because of his honorability. For, being the Vicar of Christ, he was the man in whom the whole world had confidence, the common Father of all. His honorability sustained the honor of all Christendom.

It was very common, as a consequence of this mentality, for Kings to send the Heir Princes of thrones to Popes to receive their education. The Pope would take personal care of the good formation of each of these boys. After the boy was formed, the Pope would send him back to his kingdom, thus prepared to assume the crown.

This shows the confidence that everyone had in the Papacy, the fundament of the honor of the universe.

Continued

In principle the Head of State could not take possession of his office until he had taken an oath promising to fulfill his obligations.

Today it has become an empty solemnity. The inauguration ceremony is a pretext to party and drink champagne. Very few people believe that the oaths of the Presidents of our Republics represent any substantial change to their pre-established agendas. Anyone who imagines that the political and social order of his country became much stronger because a president took his oath runs a serious risk of being considered naïve. In our days neither the ones who take the oath nor those who hear it grant any substantial importance to it.

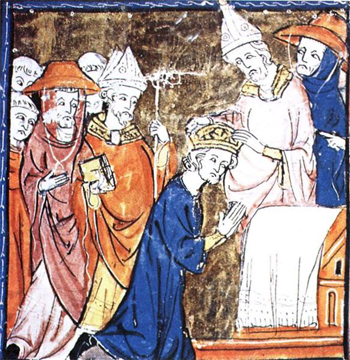

Coronation of Henry VII as Emperor in 1312

The formula of the imperial oath was variable. Each new Emperor had to commit to something more than the previous one in a ceremony called capitulation. Each Emperor had to give more guarantees that he would not limit the various liberties of his subjects. Thus, the oath of the Emperor became increasingly long and his power increasingly smaller.

In this way his subjects acquired so many rights that the Emperor became primarily a symbol. He was bound by that solemn oath and could do very little practically speaking, while his subjects became excessively independent. This process practically destroyed the Holy Empire. But no one even considered that the Emperor should violate his oath in order to increase his power. This shows the value placed on a man’s word of honor in taking an oath.

Oath of the Emperor before the Pope

Before it reached this exaggerated situation, each Emperor - either before or after his coronation - had to be crowned Rex Romanorum, King of the Romans, by the Pope or his representative. For this purpose he had to take an oath promising he would protect the Church in different ways.

The Pope or his representative would put questions to the candidate: “Will you defend the Holy Faith? Will you defend the Holy Church? Will you defend the kingdom? Will you maintain the temporal laws? Will you maintain justice? Will you show due submission to the Pope?” To each of these he responded, “I will.” The Emperor-to-be then would lay two fingers on the altar and swore his oath.

For us to understand the importance of this coronation, we have to consider that while the Church had her Papal Territories, she did not have a proportionately strong army to protect them. She relied, therefore, on the military assistance of the Emperor, who would send his troops to protect the territories if a temporal lord invaded them or oppressed the Pope.

Thus, the Pope had a special interest in crowning the future Emperor as King of the Romans. As part of the agreement, the Church agreed to pay the expenses of the imperial troops she requested. Curiously, she also would cover the expenses for the future Emperor’s trip to Rome to be crowned.

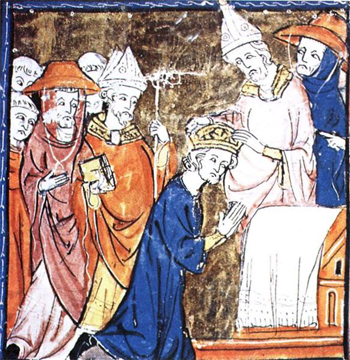

Charlemagne crowned by Pope Leo III: a significant act

As an example of the medieval oath, we have the one taken by the future Emperor Otto IV on July 12, 1198, in Aachen during the ceremony where he was crowned King of the Romans. He promised to the Archbishop of Cologne representing Pope Innocent III to protect all the rights of the Church, conserve and defend all her possessions, and help her retake from usurpers the territories she had lost. He also promised obedience to the Pope and his successors and pledged to follow the counsel and will of the Pope to maintain the good customs of the Roman people.

Shortly afterward, a delegate of the Pope delivered to Otto IV in Cologne a written papal document recognizing him “by the grace of God and the Pope” as King of the Romans. In this document the Pope threatened excommunication to anyone who violated the fulfillment of the King’s oath. This applied not only to those who would oppose the Emperor from carrying out his promises, but also to the Emperor himself, should he would break his oath.

Punishing in a dishonoring way

The seriousness given to promises was a consequence of the central role played by honor in society. The high importance of honor explains the rigor taken against those who committed crimes of dishonor. The Middle Ages with its profound juridical sense had many offenses it qualified as crimes against honor. Those were punished with penalties that touched upon the honor of the criminal, as well.

A medieval pillory, or stocks, a means to publicly dishonor a person for shameful acts

Often after such a punishment, the person was obliged to move away from that city. This was a punishment turned toward maintaining virtue and honor in society.

Other medieval cities often had a column or a pillory in a main square to which a criminal was tied facing the public. A written verdict of his crime was tacked to the pillar above his head. Thus, any person walking by could approach the pillory, read about his crime and manifest his disapproval to the criminal.

Other times it was a Pope or a King who would rigorously punish a vassal who broke his oath of fidelity. For example, Boniface VIII, who was a great Pope, had members of the Colonna family as temporal vassals. The latter revolted against him, and, as a consequence, the Pope called his faithful vassals to march against the Colonnas. The Pope’s troops went to Palestrina, one of the Colonnas’ headquarters, and razed the city to the ground.

For some of us this punishment would appear too violent. It is because we have lost the notion of honor and the horror of breaking a promise to one’s superior. We no longer comprehend the villainy of a feudal lord who would revolt against his suzerain. To restore our lost sense of honor, we would benefit from meditating on the dishonor of Judas’ treason.

It is very easy to say that Boniface VIII should have shown charity when we have lost the moral sense and do not understand the enormity of the crime of revolt, especially a revolt against the Pope.

It was this atmosphere of honor that caused the Pope to be the most respected and esteemed man in all Christendom, precisely because of his honorability. For, being the Vicar of Christ, he was the man in whom the whole world had confidence, the common Father of all. His honorability sustained the honor of all Christendom.

It was very common, as a consequence of this mentality, for Kings to send the Heir Princes of thrones to Popes to receive their education. The Pope would take personal care of the good formation of each of these boys. After the boy was formed, the Pope would send him back to his kingdom, thus prepared to assume the crown.

This shows the confidence that everyone had in the Papacy, the fundament of the honor of the universe.

Continued

Posted January 15, 2014

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Prof. Plinio

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the transcripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

______________________

______________________