|

Our Lady of Good Success

2011 Quito Pilgrimage – Part II

The Last Day of Gabriel Garcia Moreno

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

One of the highlights of my pilgrimage to Quito was to follow the footsteps of President Gabriel García Moreno, the ”truly Catholic president” Our Lady of Good Success predicted would come in the 19th century and consecrate the country to the Sacred Heart.

In a fledgling Republic dominated by liberal Freemasons who had evicted the Jesuits and were ruthlessly persecuting the Church, a statesman of different ilk entered Ecuador’s political scene in the 1860s. In the 15 years of his rule, Gabriel Garcia Moreno made that small portion of land - so dearly loved by Our Lord and Our Lady - the model of a Catholic State.

One of the last photos of Garcia Moreno (1821-1875) |

As head of State, his first priority was to re-establish for the Church all the rights that the Revolution had denied her, thereby raising the implacable hatred of the Radicals and Socialists. They called him autocratic because he refused concessions to the revolutionary party. They labeled him harsh because he rebuffed any deals with evil. “Liberty for everyone and for everything, save for evil and evildoers,” was his motto.

One of his first acts was to issue a Concordat restoring liberty to the Church. In 1867 he established a constitutional government under the Kingship of Christ. In 1870, it was Ecuador – alone among all the nations of the world – that publicly protested the invasion of the Papal States and offered a national subsidy for the captive Pope. In 1873 he formally consecrated the Republic to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

The enraged Socialists and Freemasons who lost their offices when Garcia Moreno assumed the presidency made calumny campaigns against him. But nothing succeeded in turning the people against one so honest and good. Instead, they called him “Father of the People.” Under him Catholic schools and universities prospered, the national debt was dissolved, highways and infrastructure were built, criminals were placed behind bars or hanged, and the streets were safe.

The more the people loved him, the greater the hatred of the Masons. According to biographers, there were six failed intrigues against his life after he became a major public figure in 1860.

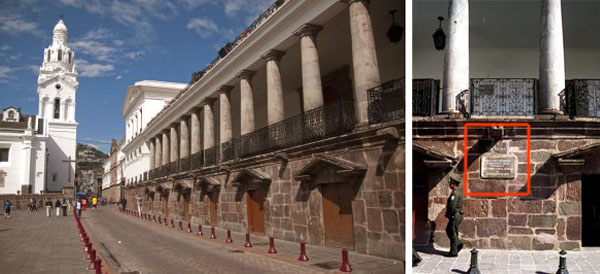

The plaque on the Presidential Palace: Here assassinated President of the Republic Dr. Gabriel Garcia Moreno fell on August 6, 1875 |

When he won re-election to the Presidency in 1875, his death was decreed by the Masonic Lodges of Germany – led by anti-Catholic Grand Master Otto von Bismarck. Warned of this danger, he wrote in his last letter to Pope Pius IX, “May I be deemed worthy to shed my blood for the cause of the Church and Catholic society.”

In early August of 1875, with preparations underway for the inaugural address as re-elected President on August 10, rumors were rife in Quito that a new plot to assassinate the President was underway. On August 5, a priest begged admittance to his office to warn him that an attack was being planned for the next day. He begged the President to take measures.

Garcia Moreno replied, “The only measure to take after calm reflection is to prepare myself to appear before God,” and he continued his work, unperturbed.

On the afternoon of August 6, Garcia Moreno was attacked by an assassin with a machete and three accomplices armed with revolvers on the porch of the Presidential Palace. Still alive he was carried to the Cathedral and died there at the feet of the altar of Our Lady of Sorrow shortly afterwards.

A lecture by an expert

Dr. Salazar, under his great-uncle's picture |

Our pilgrimage group had the good fortune to follow the last day in the life of Garcia Moreno with Dr. Francisco Salazar Alvarado as lecturer and guide. His great uncle was General Francisco Javier Salazar, Minister of War under President Garcia Moreno and his close and trusted friend. Growing up in a family where there was constant talk of Garcia Moreno, Dr. Salazar’s interest in him grew. Later, as a diplomat, professor and journalist, he delved much more deeply into the life of his hero.

He shared his findings and anecdotes with us, clearing up many discrepancies and errors in the various accounts I had read about Garcia Moreno’s death.

I invite my readers to follow in the footsteps of Garcia Moreno on that last day of his life, as I recount the lecture of Dr. Salazar to our group, which I taped and now transcribe. (1) Later that evening at his home, he permitted me to scan several photos from his private collection, some of which I will reproduce for the reader here.

His last morning

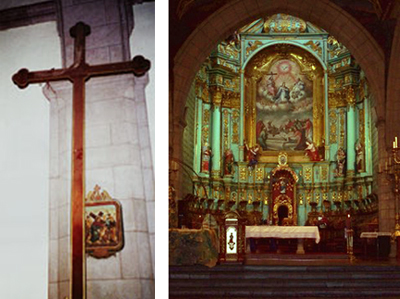

It was August 6, 1875, First Friday, the day dedicated to the Sacred Heart. The President, following his normal routine, walked from his house along one side of Santo Domingo Plaza [see picture] the short distance to Santo Domingo Church for the 6:00 a.m. Mass. In the Calvary side altar, there is a plaque that reads, “Here Dr. Gabriel Garcia Moreno received Holy Communion on First Friday, August 6, 1875, before being assassinated.”

At left, Santo Domingo plaza - his house is one of the three shown on the side of the Church; at right, a view of the Church interior |

He returned to his home to work for a while and then take a light breakfast with his wife Mariana at 9:30 a.m. He usually walked to the Presidential Palace after his meal, but that day he remained home to work on his inaugural speech he planned to deliver to Congress on August 10. The conspirators, who had planned their attack for that morning, were frustrated at this change in routine but remained resolved to attack that day.

At 1:00 p.m., he left for the Palace, accompanied only by his aide-de-camp Manuel Pallares. He stopped briefly to greet his in-laws, the Alcazar family, on Sucre Street near the Jesuit Church, la Compania. Because he had been ill and the weather was cool, he buttoned up his coat and continued on his way.

He made one more short stop, at the Cathedral, entering the chapel where the Blessed Sacrament was exposed. After this visit he left, directing himself to the Government Palace. The conspirators were ready.

At the steps of the Presidential Palace he greeted several persons, including Faustino Rayo, who would shortly strike the first brutal machete blow. Rayo, who held a grudge against Moreno for dismissing him from a lucrative office because of his dishonest practices, had taken up leatherwork. He pretended, however, to be on friendly terms with the President, who had recently contracted him to make a saddle for his young son (his only living child), Gabriel García del Alcázar.

He climbed the side stairs to the porch with its thick colonial pillars. At that time there were no railings between the columns, as we see today. In fact, the scrolled black grills came from the famous Tuilleries Palace in Paris, torn down by the revolutionaries and ordered by Garcia Moreno himself for Ecuador’s Palace. They would only arrive and be installed, however, after his death.

The Cathedral (at left) and Presidential Palace in the Grand Plaza; at right, the place where Garcia Moreno fell |

He was approaching the Treasury Department’s entrance into the Palace. There, Rayo rushed forward and attacked him with a machete. The first blow struck his hat, which flew off his head and landed in the plaza below. Rayo delivered more blows, and his fellow conspirators took position and fired their guns. Their bullets only grazed him.

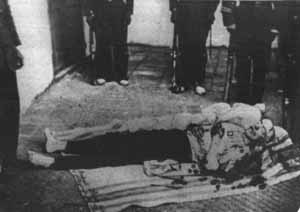

An actual photo taken of the President on the Plaza after his fall; below, a second, taken in the Cathedral

|

Afterward, the infamous cry of Rayo, “Die, tyrant!”

And the beautiful response of Garcia Moreno, staggering from the wounds, “Dios no muere!” “God does not die.” These were the last words of a line he had often repeated, “I am only a man who can be killed and replaced, but God does not die.”

Another shout came from Rayo and fellow assassin Roberto Andrade, “Die, Jesuit!” It was a way to say “Die, lover of Jesuits,” an Order that had been expelled by the anticlerical regime that preceded Moreno’s first presidency. One of his early acts in 1860 had been to invite the Jesuits back and to return their buildings.

Garcia Moreno tried to take out his revolver to defend himself, but his wounded hand made him fumble as he tried to unbutton his jacket. Rayo struck with the machete again, this time nearly severing the left arm. More shots sounded from the pistols of the other conspirators, Roberto Andrade, Manuel Cornejo and Abelardo Moncalyo. Again, their shots only grazed the body.

After Rayo’s last vicious blow, the President staggered and fell from the porch to the ground some ten to twelve feet below, landing in front of a tavern. Today on the wall over that spot is a simple stone marker. It all happened in just a few minutes, according to witnesses.

The fatal blows

His arm broke in the fall, but Garcia Moreno was still alive. The autopsy report, made shortly after his death, (2) said that up until this time he had received no fatal wounds. One cannot help but wonder: Where was the aide-de-camp Manual Pallares?

Instead of stepping forward to protect him, he had turned to run for help, leaving the President defenseless. Was he part of the plot? That was never proved, but there was little doubt in the minds of many – including the aunts of Dr. Salazar who often remarked on the incident – that he was a coward.

The hat he was wearing |

The sound of the shots had attracted the attention of the people in the square and in the military quarters across the Plaza, where General Salazar was working that day. Women from the tavern and nearby shops had rushed to the fallen President; others were milling around the scene.

Rayo and his accomplices raced down the steps to finish their shameful assignment. Pushing the women aside, Rayo struck repeated blows with his machete, including the two fatal wounds to the head, one that severed a part of his skull. More shots were fired; again the bullets only grazed the body of the President.

Shouting revolutionary slogans like “Down with tyranny,” “Now we are free,” the assassins fled. Rayo tried to make his escape also, but he was behind the others. Hearing the gunshots, General Salazar had ordered troops out into the square. Now, three soldiers grabbed the fleeing Rayo and started to march him to the military headquarters.

Above right, the Cathedral's main altar; at left on a side wall, the 20-foot cross the President carried in the Holy Week procession

Below left, Our Lady of Sorrows altar (behind the main altar) where he was laid; below right, the place - marked with a wood frame - where he died

|

The news was flying right and left: “The President has been shot and killed.” “The scoundrel Rayo is the murderer.” In the confusion, an order was heard, “Kill the assassin!”

A sergeant fired a shot and killed Rayo there in the middle of the square. In his pockets were large amounts of Peruvian currency, the Judas payment of the Masons which would allow him to flee Ecuador and live in Peru. The crowds took his body, dragging it through the streets, and left it unburied for the vultures to feed upon.

General Salazar arrived at the scene of the dying President and ordered Garcia Moreno to be taken to the Cathedral. His massacred body was placed at the feet of the shrine of Our Lady of Sorrow, to whom he had a great devotion. The priest who administered the Last Rites asked the dying President if he forgave his enemies. With effort Garcia Moreno opened his eyes, his expression affirming his assent. Shortly afterward, he expired.

On the breast of the President was a relic of the true cross, a scapular of the Passion and the Sacred Heart, and his rosary, along with a medal of Pope Pius IX. In his pocket was his copy of The Imitation of Christ, with his rule of life written on the last page [read here]. Penciled in on that page were these few words, “My Savior Jesus Christ, give me a greater love of Thee and profound humility, and teach me what I should do this day for Thy greater glory and service.”

A foiled revolution

The revolutionaries had hoped that the assassination of Garcia Moreno would spark a revolution among the people, who would rally around the Masonic ideals of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity and reject the Catholic Church. Instead, the opposite happened. The people of the nation mourned their lost President, naming him the Father and Regenerator of Ecuador and regarding him as a martyr for the Catholic Faith.

His wounds were stitched – amazingly, no vital organ was severed in the brutal attack – and his body was dressed in full ceremonial uniform and set up in a chair in the corner of the second floor of the Cathedral courtyard. A five-man honor guard took up position behind him, and the people traveled for miles to process past his corpse and pay him homage.

A rare photo of Garcia Moreno's corpse with the honor guard in the Cathedral courtyard; at right,the corner with a marker as it appears today

|

At the funeral on Sunday, Garcia Moreno’s body was also set up in a chair, facing the audience, as a high tribute to the fallen President. He was buried in the Cathedral, but his body did not find a final peace there.

Eight years later, with the country in revolutionary chaos, the friends and family of Garcia Moreno feared his remains could be removed and desecrated by the Liberals. In the middle of the night, they removed his corpse and placed it in a hidden place, unknown to the world until Dr. Salazar entered the history of Garcia Moreno in 1973 and began his quest to discover it.

His great adventure will be related in the next article.

1. For some details, I referred to Dr. Salazar’s book, Encuentro con la historia: Garcia Moreno, líder católico de Latinoamérica [Encounter With History: Garcia Moreno, Catholic Leader of Latin America], available in Spanish in English from Our Lady of Good Success Apostolate. I also referred to the scholarly work Gabriel García Moreno and Conservative State Formation in the Andes by Peter V. N. Henderson (University of Texas Press, 2008).

2. An official report of the autopsy made at 5 p.m. that afternoon can be found in Encounter with History, Documents section, pp. 178-182, or, in the Spanish copy Encuentro con la historia, pp. 227-234.

Continued

Posted February 25, 2011

Related Topics of Interest

Part I: Impressions of Our Lady of Good Success Part I: Impressions of Our Lady of Good Success

Part III: Impressions of Our Lady of Good Success Part III: Impressions of Our Lady of Good Success

Part IV: The Search for Garcia Moreno's Body Ends Part IV: The Search for Garcia Moreno's Body Ends

Part V: "My Sons, I Am Poisoned" Part V: "My Sons, I Am Poisoned"

Garcia Moreno – Model of a Catholic Statesman Garcia Moreno – Model of a Catholic Statesman

The Prophetic Mission of Mother Mariana The Prophetic Mission of Mother Mariana

Prophecies of Fatima and Our Lady of Good Success Prophecies of Fatima and Our Lady of Good Success

The Christ Child of Pinchincha The Christ Child of Pinchincha

Our Lady of the Cloud in Quito Our Lady of the Cloud in Quito

Ecuador, a Nation that Is a Reliquary Ecuador, a Nation that Is a Reliquary

Our Lady of Good Success Home Page Our Lady of Good Success Home Page

Related Works of Interest

|

Our Lady Good Success | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|