|

Religious: Ven. Antonio Margil

Ven. Antonio Margil of Jesus:

Apostle of New Spain and Texas

Marian T. Horvat

The barefoot friar -

famous for his missionary work and miracles

|

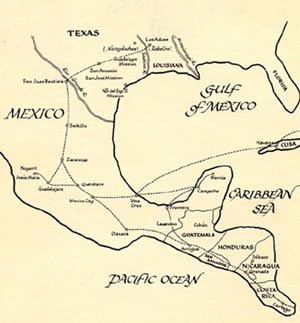

The life of Fr. Antonio Margil of Jesus is an epic story of a man who seems larger than life. Barefoot, carrying only a staff, breviary, and the materials he needed to say Mass, he established hundreds of missions in a territory extending from the jungles of Costa Rica to east Texas and the borders of Louisiana. Countless Indians of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Mexico and Texas received the divine gift of faith from him and revered him a saint. For this, he is called the Apostle of New Spain and Texas. (1)

(1) The main works used in this article are, Ubaldus da Rieti, O.F.M., Life of Venerable Fr. Anthony Margil, Taken from the process for his Beatification and Canonization (Quebec/NY: Franciscan Missionary Printing Press, 1910); Eduardo Enrique Rios, Life of Fray Antonio Margil, O.F.M., trans. by Benedict Leutenegger, O.F.M. (Washington D.D.: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959); Nothingness Itself: Select Writings of Ven Fr. Antonio Margil, O.F.M., (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1976).

He was also an extraordinarily capable administrator and founded two colleges in Guatemala and Mexico. His name is associated with the epoch of mission colleges, which made possible a rebirth of the Franciscan apostolate, first in Mexico, and later in Guatemala, Panama, and most of South America. In effect, a second golden age for the Franciscans in Spanish America began with the foundation of the colleges, centers established by the Holy Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith to train new missionaries and establish mission churches and settlements.

This “barefoot friar,” famous in his time for his miracles and sanctity, converted hundreds of thousands of Indians. In Guatemala alone, it is recorded that he converted over 80,000 Indians. He became known as the “Flying Father” because he would cover so many miles in such short periods of time it was nothing short of miraculous: it was normal for him to cover 40-50 miles a day over rough terrain, and often more. There are written testimonies of companion brethren and soldiers who saw him, quite literally, walk on water, as he crossed swollen streams and rivers on his apostolic journeys. This capacity to pass from place to place with great speed is known as the gift of agility.

Along his travels, he cured the sick, read souls, prophesied the future. God also granted Fr. Margil the gifts of bilocation, to be present in two places at the same time, and subtility, which enabled him to enter dwellings through closed doors. Like St. Anthony of Padua, he even received marks of veneration from animals. Once when he was directing the building of a missionary College in Guatemala, some Indians arrived with twelve cartloads of stone. Fr. Margil addressed them and blessed them. The Indians knelt and, at the same time, the animals drawing the carts fell to their knees. It is small wonder the fame of this illustrious missionary spread far and wide.

What is more difficult to understand is why Fr. Antonio Margil is not better known today. It is my hope this article will make him better known to the North American Catholics, and that they may begin to invoke the great Apostle of Texas in their needs.

Epoch One: 1657-1684

On August 18, 1657, Antonio Margil was born in Valencia to poor but pious parents, Juan Margil and Speranza Ros. Margil was blessed from childhood with an affable and good nature. Small of stature, the boy had a natural charm, and was attracted to practices of piety and study. Despite their humble means, his parents took care that he should receive the best education possible.

At age 15, Antonio entered the Franciscan novitiate at Corna Monastery in Valencia, and two years later made his first vows. It was there he chose for himself the pseudonym La Misma Nada – Nothingness Itself. He made it his practice from that time on to conclude his letters by writing the words “La Misma Nada” above his name and signature.

After pronouncing final vows, he devoted himself to the study of Philosophy and Theology in the Monastery of Denia and the Royal Monastery of Valencia. During this time, he began the rigid regime he never abandoned his whole life. Every night in the convent garden he performed the pious exercise of the Way of the Cross, carrying a heavy Cross. Afterward, he scourged his body with an iron chain, saying that a religious of St. Francis ought to be fervently devoted to the sufferings of Christ. He practiced a poverty so exact that he often deprived himself of even the necessary things. Amiable with all, he allowed himself no particular friendships, and no shadow of singularity or affectation. It is no surprise that after his death those who had studied with him testified that they had looked upon him as a saint even at this time.

Having completed his studies, he was ordained a priest at age 25. He had asked to remain a friar, like his holy Father Francis, considering himself unworthy of the great privilege of receiving full orders, but his superiors counseled otherwise. The fruits of his preaching and hearing confessions began to appear very soon afterward. Great crowds gathered in the public square of Valencia to listen to him, his words arousing them to tears and repentance. Sometime he spent whole nights in the confessional. Had he remained in Spain, it is no doubt he would have been a renowned preacher and theologian. But Fray Margil was destined for a greater and nobler mission.

To the New World

In 1682, Ven. Fr. Antonio Llinas, Franciscan superior of the American Mission, invited Fr. Margil to be his companion to open the first missionary college in New Spain at Querétaro, Mexico (200 miles north of Mexico City). He immediately consented. Later Fr. Llinas would say that he had brought to America a second St. Anthony of Padua.

With the permission of his superiors, he made a farewell visit to his mother, worthy of mention. She wept bitterly at thought her son was to leave her, and entreated him to consider her advanced age and wait a few years so she might have the consolation of expiring in his arms.

The son did not waver in face of these entreaties. Kindly he reminded her that from the moment she consented he should enter religion, he belonged entirely to God, Who had called him to promote His honor and glory among the pagans. He gave her a Franciscan habit and told her to clothe herself with it and call upon him when death approached.

In fact, shortly after his departure, his mother was stricken with an illness bringing her to the point of death. She did not forget his promise and called on her son. By God’s permission, her son appeared to her, assuring her of recovery, which immediately followed. A few years later when her end in truth approached, Fr. Antonio Margil, by a prodigy of Divine Providence, assisted at her bedside and consoled her in the hour of death in the presence of many persons, even though they were separated by an immense distance.

Epoch Two: 1683-1714

Apostle of New Spain

The barefoot friar - famous for his missionary work and miracles

|

The barefoot friar - famous for his missionary work and miracles

|

The barefoot friar - famous for his missionary work and miracles

|

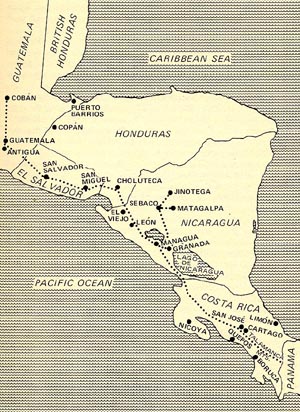

The great odyssey of evangelization began in 1684 when Fr. Margil set out from Santa Cruz College in Querétaro with another Franciscan missionary giant, Fr. Melchor Lopez, who would be his traveling companion for the next ten years. From town to town they traveled, giving missions for a year along the shores of Guatemala. From there, they set out for provinces of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, converting many pagans along the way, and re-catechizing and increasing the fervor of those already Catholic.

Preaching to whomever they met, they walked along, praying in silence or singing. Fr. Margil always walked barefoot, but carried his sandals so he could wear them for Holy Mass out of respect for the Blessed Sacrament. Everywhere he went, he taught his famous “Alabado,” a song in verse written to catechize the Indians and Spanish children. It is still remembered and sung today in parts of Mexico, Central and South America. Its last verse reads:

“Whoever seeks to follow God and strives to enter in His glory, One thing he must do and say with all his heart: Die rather than sin. Rather than sin, die!”

When they reached a village where they found welcome, they would establish a mission church. The Indians would be taught the catechism, the Rosary, and the Way of the Cross. Other friars would come to replace the first ones and to care for the new Catholics. Before they left, Fr. Margil would plant a wooden cross, as high as he could make it. Then the missionaries would continue onward. Fr. Margil and Fr. Melchor came to be venerated so much that when the priests would leave a village, often the Indians would follow them in crowds of hundreds, carrying branches of trees in their hands, appearing like moving forests from a distance.

Mission among the Talamancas: Miracle Worker

From Guatemala, Fr. Margil and Fr. Melchor set out to preach among the Talamanca Indians of Costa Rica. The Talamancas were a mountain dwelling Indian people, actually three nations of Indians famed for their ferocity, human sacrifices, and obstinacy to missionaries.

In particular, the shamans, or witch doctors, put every obstacle in the way to prevent the missionaries from preaching the Gospel of Christ. On one occasion in this region, Fr. Margil was taken prisoner and the shamans instigated the warriors to cast him into a pile of burning wood. The fire was maintained for several hours but the flames did not injure him, even though they blackened the image of the crucifix he held in his hand. On another occasion, Indians of a mountain town poisoned their food, which the missionaries blessed and ate, and came to no harm. Another time they were on the point of being burned at the stake, but the wood refused to burn. Such prodigies increased the fury of the medicine men, but opened the hearts of many of the Indians.

The missionaries suffered these things and more joyfully, their undaunted spirit and great courage earning them the admiration and awe of the Indians. “We suffered what the Lord was pleased to send us,” Fr. Margil later wrote. His only complaint was a sigh of regret not to have gained the crown of martyrdom.

When the Indians realized the utter indifference of the friars toward earthly goods and their great charity toward even those who ill-treated them, they came to trust and love the friars. One of first things Fr. Margil did was successfully petition the government that none of his Talamanca Indians should be taken for work on nearby haciendas, so that the fruit of their missionary labor might not be nullified. In a letter to the president of the Audiencia of Guatemala, Fr. Margil wrote: “Through all this region, called Talamanca, all the tribes say that they will persevere as long as the Spaniards do not come to rule over them; they shall welcome only the priests.”

In the course of two years, he and a single companion, working together and alone, had erected 15 mission churches (some say 30), and baptized hundreds of Indians.

With this success, the pair next decided to go among another unconquered and feared tribe, the Terrabi. Already, the fame of Fr. Antonio Margil was such that when he sent ambassadors to the eight Terrabi chiefs to request permission to enter their territory and preach the Gospel of Christ, seven readily consented.

One, however, refused, declaring before his idols he would slay any missionary who should venture into his territory. The bold response of Fr. Margil unnerved him. Instead of retreating or opening negotiations, Fr. Margil forthright entered his camp, where a war party was being prepared, and went straight to the abode of the chief. Overcome by the sight of this small but intrepid man, shining with a kind of a supernatural light, the chief laid his weapons at Fr. Margil’s feet and received the missionary with demonstrations of affection and honor. This was the effect of the person of Fr. Antonio Margil.

His reputation for discovering false idols was such that in many Indian villages, when word would arrive that Fr. Antonio Margil was coming, they would gather beforehand their false gods for him to burn. They had much experience with the futility of trying to fool the holy friar, who would unearth their idols straight away by a special grace from God. All these idols and charms were then burned in an open place and in the presence of Fr. Margil and Mr. Melchor, who did public penance in reparation to Our Lord for these sins of superstition.

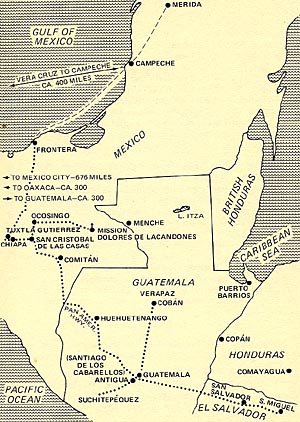

Missions to the Chols and Lacondons

As the name of Fr. Margil and the wonders he performed were on all lips, the Bishop of Guatemala asked that he be sent north to the lands of the Chols, a violent tribe who had rebelled against the efforts of the Dominican missionaries. Their religious instruction proved so fruitful that the greater number of them was converted. Eight towns with churches were established among the Chols.

Their next mission was along the border of Mexico among the Lacandons. When the missionaries arrived there, even their guides abandoned them, fearful of these naked savages with reputations of being cannibals. Entering their territory, the missionaries were seized, stripped of their habits, bound to trees and commanded under pain of death to worship their idols. They refused, and preached instead the Gospel. For the three days the men were bound to the posts and tortured, they waited to receive the palm of martyrdom. When the Indians discovered the missionaries were always cheerful and without fear, they believed they concealed something extraordinary in their hearts. At length they released them, on the condition that they leave the place immediately.

Seeing their efforts were of no avail, the missionaries left the place. Before they departed the main village, however, Fr. Margil warned the people that God would punish them shortly with a catastrophe. The prediction was soon verified, for their houses were destroyed by a fire that came from heaven.

Some months later, accompanying a military expiation opening a road between the Yucatan and Guatemala, Fr. Margil again had opportunity to enter this area. This time, awed by his reputation and won by his kindness, great numbers of the fierce Lacandons came to him, asking to be baptized. Many of the sick here, as in other villages, were healed by the imposition of his hands or the reading of the Gospel of St. John. Of the many miracles performed among the Lacandons, one in particular is worthy of mention.

Among the newly converted, Fr. Margil introduced the pious custom of greeting a person saying “Hail Mary,” which was answered by “Conceived without original sin.” One day Fr. Margil met an Indian woman carrying an infant, still too young to speak. Approaching her in the presence of many persons, he said to the baby: “Hail Mary.” Immediately the infant answered: “Conceived without original sin.” In a marvelous way, the babe attested the singular privilege of the Mother of God, as well as the sanctity of Fr. Antonio Margil.

The soldiers on this expedition witnessed many such marvels. Despite the fact that Fr. Margil always remained far behind the expedition in order to hear confessions and teach catechism to the Lacandons, at the end of the day he arrived at the arranged meeting place ahead of the troops. When the Father Commissary questioned him about how he had passed the men who were traveling on horses, he answered smiling, “I take short cuts and God helps.”

The rumor was also spreading that his feet did not get wet when he crossed the swollen streams and riverbeds. One day a soldier in the expedition pretended he was tired and sleeping on the bank so he could discover how Fr. Margil would cross the turbulent river. Margil noticed the man and understood his intent. He walked over the water and came alongside the soldier. Smiling paternally, he said, “Now that you have seen it, move along.”

The Indians had a simple explanation for such wonders: they called Fr. Margil “santo” and would not desist, even when he reprimanded them. Before he left the Lacandons, Fr. Margil had erected two churches and installed all the pious customs he loved, the Rosary, morning and evening prayers, the Stations, and public processions on feast days.

1697-1714 Founder and Administrator

In 1697, Fr. Margil was recalled to Querétaro as superior, or presidente, of the Franciscan College of the Holy Cross, and a new phase of his life began as an administrator. When he reached the College, Fr. Margil took off the ragged habit he had worn and mended for 14 years, patching it at times with bark from a certain tree called the mastastes, and exchanged it for a new one, thus avoiding the least shadow of singularity.

As superior, he never dispensed himself from any public act or expected anything but what he himself practiced. To maintain accuracy and the decorum of ritual, he imposed upon his religious the obligation of holding a conference once a week on the ceremonies of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. The friar who loved “Lady Poverty” exhorted his brethren and the faithful to ornament the altars and churches as much as they could so they might be worthy of the divine majesty of God.

His mortifications and gifts

For Our Lord, there was nothing too rich or decorous. For himself, it was a different story. With the exception of Sunday, he fasted every day, taking a few herbs, a piece of bread, and some water or watered down chocolate once a day. He permitted himself sleep only from 8 to 11 every evening. He was wakened then by the brother porter, and together they read a chapter from The Mystical City of God by María de Agreda. After praying the Divine Office at midnight, he made the Stations and scourged himself, and would remain in prayer until the hour of Prime, absorbed in God.

It was clear to all that Heaven smiled on the humble Franciscan. Ecstasies were habitual to Fr. Margil, who was seen raised into the air in his prayer. Fr. Simon de Kierro, a faithful companion for many years, solemnly testified that more than once he had seen him elevated several feet in the air while celebrating Mass.

His confessional was always crowded as persons learned of his rare ability to read souls and discover secret sins. For example, a soldier living in a fort in Texas could not free himself of habits of lust and impurity, and had abandoned himself to a life of vice. One day, hearing Fr. Antonio Margil preach, he desired to have recourse to him, but feared to expose his immoral conduct to a man so pure and holy.

Fr. Margil, inspired by God, called the soldier by name, and encouraged him to make a confession. The soldier made a good confession, lived 40 more years, and attested he had never committed a sin against purity since his confession to Fr. Margil.

His countenance portrayed his virginal purity, shining with the radiance of a burning light. He admitted that in the confessional when penitents entered, he could distinguish those who had been impure, and he was endowed with the rare gift of banishing all impure thoughts and desires from the hearts of those who approached him.

He had the gift of prophecy, especially in reading vocations. At the end of his first visit to the Secretary of War in Guadalajara, Don Juan Martinez de Soria, Fr. Margil asked, “Where is the Little Sister of St. Clare?” Don Juan replied there was none there. Fr. Margil smiled and entering a room where the children were playing, he fixed his gaze on a child, saying, “Behold the little sister of St. Clare.” In fact, the girl became a St. Clare sister, lived a holy and edifying life, and died in the odor of sanctity at age 75.

It was not uncommon for Fr. Margil, upon seeing a boy for the first time, for him to tell the mother or father, “This one belongs to me.” Such prophecies were verified in every case.

Like another Jerimiah, he also often prophesied doom for those who would not heed his words. Once he was preaching in Mexico City, speaking with great zeal against the immoral productions presented in a theater near the church. He warned that God Almighty would soon send down fire to destroy that place where so many sins were committed. That same night, the building was reduced to ashes.

More appointments

Seeing the graces and favors bestowed by God upon Fr. Margil and those around him, he was asked to found the College of Christ Crucified at Guatemala, and was elected its first Guardian in 1701. He personally oversaw the construction of the edifice, again working many miracles. Once he ordered a group of children to leave a mortar ditch where they were playing. A few seconds later a pile of dirt fell on it and submerged it. Another time, he bilocated to the work site and stopped a heavy rock from crushing one of the workmen. Astonished by what they saw, the laborers united prayer with their work, substituting the recitation of the Rosary for the normal idle conversation.

As soon as his term as superior ended in 1705, Fr. Margil was appointed commissary of the missions of Costa Rica. Shortly afterward, he was appointed to found another new mission college in Zacatecas, Mexico. In need of financing for this new college, which was in a poor and barren area, he encouraged a benefactor to open a long abandoned silver mine, promising it would yield an abundance of silver. His prophecy proved correct, and the benefactor could defray all the expenses of the building of the College of Our Lady of Guadalupe of Zacatecas, as well as the church and monastery annexed to it.

In November 1713, a new superior of the college was elected, leaving Fr. Margil again free to dedicate himself fully to his missionary labors among the Indians. At an age when many men are dreaming of retirement and relaxation, the almost 60-year-old friar, stooped and worn from a life of hardship and mortification, was ready to embark on the third and last epoch of his life, the founding of missions in Texas.

(1) The main works used in this article are, Ubaldus da Rieti, O.F.M., Life of Venerable Fr. Anthony Margil, Taken from the process for his Beatification and Canonization (Quebec/NY: Franciscan Missionary Printing Press, 1910); Eduardo Enrique Rios, Life of Fray Antonio Margil, O.F.M., trans. by Benedict Leutenegger, O.F.M. (Washington D.D.: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959); Nothingness Itself: Select Writings of Ven Fr. Antonio Margil, O.F.M., (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1976).

This is an epic tale of a man who seems larger than life. But, let me be clear, it is not a tale – it is a real story, it is American history, unfortunately part of the story usually not taught in US classrooms in American History classes. In the minds of many, in fact, the story of the United States is simply Jamestown, the Boston Tea Party, the American Revolution and the 13 original states of the North, with a side note on the North American Jesuit martyrs.

Third order Franciscan Christopher Columbus

|

Lost to History – or distorted by anti-Catholic revisionist historians – are the Spanish colonizing efforts in the lower half of the United States as well as its principal motives. A primary motivation for the great adventure of third order Franciscan Christopher Columbus was, without a doubt, the propagation of the Catholic Faith when he landed in the continent of America on October 12, 1492.

On his second voyage, he was accompanied by Benedictine, a Jeronymite, and three Franciscan priests. Thenceforward, hundreds of zealous missionary priests, first the Franciscans in 1524, and soon afterward the Dominicans, Augustinians, Jesuits and others, came to the New World to evangelize the natives. They were supported by legislation of Popes and kings, which prescribed that those who would colonize the obligation to spread the Gospel and bring the Indians into the Catholic Church.

Multitudes of Indians embraced the religion of Jesus Christ through the zeal of missionaries, many of whom gave their lives for the faith. Some became renowned for their great sanctity, such as St. Turibius of Lima, St. Francis Solano of Peru, the Jesuit St. Peter Claver.

In the United States, many have heard of the Jesuit Fr. Eusebio Kino, who entered Arizona in 1700 and founded San Xavier del Bac near Tuscon. One of the best known missionaries, of course, is Blessed Junípero Serra, who entered California in 1769 and began the founding of the 21 California missions. Many books have been written in English about this capable administrator and holy missionary, and most American Catholics know something about him.

Ven. Antonio Margil labored among the Indians of Central America, Mexico and Texas, converting thousands.

|

But a quarter century before Fr. Serra began his California venture, there was another extraordinary Franciscan carrying out a super-human work of evangelization across Central America, Mexico, and finally, Texas. He was a miracle worker, a barefoot friar who traveled as far south as Panama and as far north as the Texas/Louisiana border and converted many thousands of Indians.

He became known as the “Flying Father” because he would cover so many miles in such short periods of time it was nothing short of miraculous, it was normal for him to cover 40-50 miles a day, and often more. There are other written testimonies of companion brethren and soldiers who saw him, quite literally, walk on water, as he crossed swollen streams and rivers on his apostolic journeys. This capacity to pass from place to place with great speed is known as the gift of agility.

In his zeal to spread the Catholic faith, he faced the heat of deserts, cold of mountains, roughness of roads, lack of proper nourishment, privations of every kind, the witchcraft of people, the cruelty of the Indians infidels. More than once he was tortured, beaten, or left for dead. His name, which deserves to be known and his fame spread, is Venerable Antonio Margil de Jesus.

A miracle worker, he cured the sick, read souls, prophesied the future. In addition to the gift of agility, God granted Fr. Margil the gift of bilocation, to be present in two places at the same time, and the gift of subtility, which enabled him to enter dwellings through closed doors. Like St. Anthony of Padua, he even received marks of veneration from irrational animals. Once when he was directing the building of the College for the Propagation of the Faith in Guatemala, some Indians arrived with twelve cartloads of stone. Fr. Margil addressed them and blessed them. The Indians knelt, and at the same time the animals that drew the cars fell to their knees. It is small wonder the fame of this illustrious missionary who called himself “God’s donkey” spread far and wide.

Barefoot, carrying only a staff, breviary, gourd of water and the materials he needed to say Mass, he established hundreds of missions in a territory extending from the jungles of Costa Rica to east Texas and the borders of Louisiana. Countless Indians of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Mexico and Texas received the divine gift of faith from him and revered him a saint. For this, he is called the Apostle of New Spain and Texas.

At the same time, he was an extraordinarily capable administrator and founder of two colleges in New Spain. His name is associated with the epoch of mission colleges, which made possible a rebirth of the Franciscan apostolate, first in Mexico, and later in Guatemala, Panama, and most of South America. In effect, a second golden age for the Franciscans in Spanish America began with the foundation of the missionary colleges, centers established by the Holy Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith to train new missionaries, preach missions to the converted, and establish new missions among the Indians in unexplored territories.

This revival of a lagging missionary apostolate was in large measure due to the efforts of Fray Antonio Margil, who, more than any other, made the mission college a reality, giving it shape and form with the foundation of these first colleges of Querétaro, Guatemala and Zacatecas. His reputation and virtue won important friends and donors; his learning wrote the missionary manuals; his spirit and example inspired his fellow friars. In fact, Fr. Antonio Margil was the hero and model ideal of a missionary for Fr. Serra, who was trained a quarter century later in the mission college of Mexico City.

The life of Fr. Margil is a splendid epic and interesting from every point of view.

|

The life of Fr. Margil is indeed a splendid epic and interesting from every point of view. After the intervention of Lady of Guadalupe in 1531, one can assert that perhaps no one individual did more to spread the Gospel in New Spain than this simple Franciscan priest, Antonio Margil de Jesus, who titled himself and signed every letter as El Nada Miasma – Nothingness Itself.

I have read many accounts of Fr. Margil, and I noticed that in the effort to follow his movement and record his appointments, his biographers often are reduced to highlighting what he did and where he went. Less space, almost by necessity, is given to his gifts and miracles.

Therefore, in the talk on this tape, Ven. Antonio Margil, Apostle of Texas, I will try to emphasize his virtues, gifts and miracles and present them to view of the faithful, so that they can glimpse the supernatural dimensions of Fr. Antonio Margil of Jesus. In the United States, we do not have the luxury of a great number of saints. In some Catholic Latin American countries, for example, Ecuador, there are saints for almost every city, accounts of miracles and marvels to be found on every corner, the heavens seem a bit closer to earth.

Therefore, when we find a spot where a saint touched the earth here in the United States, we should treasure it and reap the benefits of such gifts from Heaven. This is our Catholic history, these are our real heroes, these are the saints who shared our soil, who Our Lady wants us to develop a relation with, to call on in our needs because she put them in our pathway.

One of these saints in Ven. Antonio Margil, Apostle of Texas.

Click here to purchase tape

Ven. Antonio Margil, Apostle of Texas

|

Margil Main Page | Religious Main Page | Home Page | Books | CDs | Contact Us

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|