|

Ven. Antonio

Margil

Ven. Antonio Margil of Jesus:

The Apostle of Texas

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

A quarter century before Fr. Junípero Serra began his California adventure, there was an extraordinary Franciscan carrying out a great work of evangelization across Central America, Mexico, and finally, Texas. In his zeal to spread the Catholic faith, he faced inclement weather, hostile animals, forest insects and reptiles, lack of food and water, and cruel treatment from hostile Indian tribes.

The barefoot friar who walked on water in his extraordinary missionary work |

More than once he was tortured, beaten, or left for dead. His name, which deserves to be known and his fame spread is Venerable Antonio Margil de Jesus, who titled himself and signed every letter as El Nada Mismo – Nothingness Itself.

In the United States, we do not have the luxury of a great plenitude of saints. In some Catholic Latin American countries, there are saints for almost every city, accounts of miracles and marvels on every corner, the heavens seem a bit closer to earth. Therefore, when we find a spot where a saint touched the earth here in the United States, we should treasure it and reap the benefits of such gifts from Heaven. This is our Catholic history, these are our real heroes, these are the saints who shared our soil, who Our Lady wants us to develop a relation with, to call on in our needs because she put them in our pathway. One of these marvels is Fr. Antonio Margil.

The postulator for the Cause of Ven Antonio Margil divided his life into three epochs. The first was from 1657, his birth, until his journey to the New World, 1684. The second began with the establishment of the Mission College of Querétaro (Mexico) and his first missions in Guatemala in 1685 until 1716, after he had founded two new colleges in Nicaragua and Mexico. The third and last epoch begins with his Texas missions in the year 1716 , and ends with his death in Mexico City in 1726.

Mission to Texas: 1716-1726

What is most interesting about the Texas missions is that one could say that this was the only assignment Fr. Margil chose himself. All his life, he lived under holy obedience. He wrote that he had “never undertaken any enterprise, not even a step, without permission.” Often poorly considered orders compelled him to leave his missions when the missionaries were on the very brink of reaping the harvest of their preaching and labors. But Fr. Margil never hesitated to abandon enterprises and every hope of success, and travel hundreds of miles through the roughest and most dangerous country, to obey the order of his superiors.

In 1714, however, he had been appointed vice-commissary of the missions of New Spain and had been granted an apostolic faculty to give missions wherever he deemed proper and with those companions who seemed to him best qualified for the accomplishment of this work. He had heard of the plight of the Indians of Texas, ignorant of the true Faith, and living in deplorable and brutish conditions. Now, at almost the age of 60, he was intent upon making the difficult journey there to found missions and convert them.

His five years of work in Texas, only a little over a year in San Antonio, where his name is best remembered, could be itself a lifetime’s work, but it was just a fraction of all he did in his 43 years of work as a missionary in Central and North America. In a certain way, the years in Texas constituted the crown of the glories and sufferings of his lifetime.

Difficult beginnings

Threatened by French encroachments from Louisiana onto Spanish territories, Spain had stepped up its colonization and the Franciscans had established a mission in Texas in 1690. But it had lasted only three years. Because the conditions for colonizers were bleak and difficult, the government was not concerned about its colonization and progress. The friars had to contend with so many difficulties, exorbitant costs, and losses that Fr. Isidro Félix de Espinosa reported in his chronicle, Nuevas Empresas, “The very name of Texas had become odious to the religious.” (1)

1. Eduardo Enrique Rios, Life of Fray Antonio Margil, O.F.M., trans. By Benedict Leutenegger, O.F.M. (Washington D.D.: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959), p. 57.

Other works used in this article include: Ubaldus da Rieti, O.F.M., Life of Venerable Fr. Anthony Margil, Taken from the process for his Beatification and Canonization (Quebec/NY: Franciscan Missionary Printing Press, 1910); Eduardo Enrique Rios, Life of Fray Antonio Margil, O.F.M., trans. by Benedict Leutenegger, O.F.M. (Washington D.D.: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959); Nothingness Itself: Select Writings of Ven Fr. Antonio Margil, O.F.M., (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1976).

Fr. Margil faced a first major obstacle standing in the way of an expedition. A presidio, or military post, had to be established at the entrance to the provinces to afford escorts to the missionaries and render assistance in case of uprisings or attacks. Funds were needed for this purpose, and the royal treasury was exhausted from wars. As usual, Fr. Margil relied on Providence, which supplied in a remarkable way.

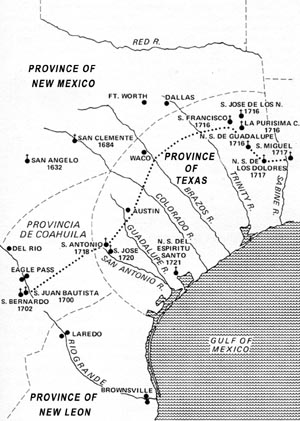

The heavy dotted lines indicate the primary route of Fr. Margil. |

Because of his reputation and popularity among the soldiers, each member of the garrison voluntarily offered him out of his pay $25 a year for life, and with this money he financed the presidio of St. John the Baptist on the Rio Grande. The way to Texas was opened.

At the beginning of 1716, an expedition party of 25 soldiers with their families set out set out for the 2,000 mile trek from Nicaragua to Texas. They were accompanied by friars from the Colleges of Querétaro and Zacatecas. Fr. Margil led the party from the Zacatecas College, and Fr. Espinosa was appointed head of the Querétaro College missionaries. Each of the colleges was to establish three missions.

As with many ventures God desires to bless, the beginnings were difficult, and for a while it seemed Fr. Margil would not even make it to Texas. Weary from the labor of the preparations, he took a fever at the very onset of the expedition and could hardly walk. When they reached the Rio Grande, he barely managed to cross, and received the Last Sacraments. The rest of the missionary party, mourning, left him to die with only a lay brother to attend him so that they could continue on with the soldiers, who could wait no longer.

But Fr. Margil did not die. He slowly recovered, and in June set out to regain the party. By the time he rejoined them in July, the first of the Zacatecas missions, the Mission of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Nacogdoches, Texas, had been founded.

The stream at the crossing of Lanana Creek, Louisiana |

In 1717, Fr. Margil established the second, Mission San Miguel, near present-day Robeline. Thus he had the honor to erect the first church building in what is now the State of Louisiana. Shortly afterward, he also established Mission Nuestra Señora de los Dolores near San Augustine, Texas, halfway between the two, and resided there.

A memorial to one of the miracles he performed during this time still exists at a crossing of Lanana Creek. During a journey from Nacogdoches to an outlying village, his group was exhausted and faint with thirst, with no hope of finding water.

Fr. Margil addressed his companions:

“Fear not, do not be dismayed. Trust in God, for in a short time you shall have water.”

Then striking a rock in the dry creek bed twice with his staff, fresh and clear water gushed forth and continues to flow to this day. The place was named the Little Eyes of Fr. Antonio Margil.

More troubles and false promises

The most testing problems the missionaries faced in Texas were not the difficult terrain or savage character of the inhabitants. First and most trying, they had to contend with the false promises and treachery of the Spanish captains, who enriched themselves in Texas while the missions suffered from lack of the most basic food and supplies. Second, they faced the French soldiers, who were vying with the Spanish for control of the territory.

In fact, with the Texas Indians, the simple weapon Fr. Margil employed was kindness. On every occasion and for every need, he was at hand. He ploughed and sowed their gardens, procured fruits, nuts and other products for their enjoyment, relieved their fatigue by doing their work. He liberally gave his services to obtain his end, to harvest a great wealth of souls.

Nonetheless, having won the Indians of that area to hear the preaching of the true Faith, he felt all the more keenly how crucial the provisions were to sustain the missions. But the promised help did not come. In a report of the missions to the Mexican Viceroy in February 1718, he wrote: “All this will perish if help does not come immediately.”

Two years passed without receiving help from any source. Failed crops worsened the situation. There were always promises of help from the Texas governor, but nothing ever came. Finally, the six missionaries met and decided to send two of their members to make a report of the actual situation. In fact, Fr. Mattias spent three months in Mexico City, but could not succeed in making the authorities understand the urgent need for soldiers and supplies to sustain the Spanish Texas settlements, especially in the northeastern missions of Fr. Margil where the French were already building forts and trading guns for horses to gain the good will of the Indians.

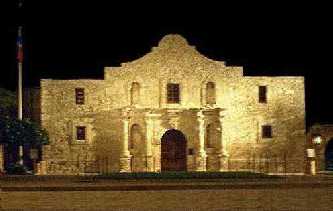

To make matters worse, in 1719, France declared war on Spain. As soon as the French garrisons in Louisiana learned of this, they attacked Mission San Miguel in Robeline. Fr. Margil was forced to abandon his missions and withdraw to the Mission of the Immaculate Conception, one of the three missions of the Querétaro College that had been established around San Antonio. Finally, it was also abandoned for the more secure Mission of San Antonio de Valero, better known today as the Alamo, founded in 1718 by Fr. Isidro Félix de Espinosa.

Above, The Mission of San Antonio de Valero, better known as El Alamo

Below, Mission of San Jose founded by Fr. Margil in 1720

|

Fr. Margil and his small band were at the Alamo mission from December 1719 to March of 1721. He took advantage of the time to write a dictionary of the various dialects spoken by the Indians of this vast territory. And he founded on the banks of the San Antonio River the Mission of San Jose, which prospered and came to be the most beautiful mission of Texas, the “Queen of the Texas Missions,” as it is called today.

He never gave up hope of recovery of his lost missions, first, as he wrote, “for God and for love of souls,” and second, “so that they may not say it was lost because of us or that it was not recovered by us.” The opportunity came in April 1721, when large expeditionary forces of a new governor arrived. Fr. Margil had the pleasure of seeing those missions restored one by one. He had already founded another mission dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe of the Bay and was intending to go further when news arrived in 1722 from the College of Zacatecas that he had been elected again as Superior for a three year term.

He had found delight in the silence and broad expanse of the land, and had written in his letters to his brethren missionaries that he hoped to die here, a simple friar, small and forgotten among his Indians of Texas. Instead, he set out on the long return trek to again take up the burden of superior in Zacatecas.

His death and miracles

Five months after Fr. Margil left Texas, he conducted a great mission in Zacatecas that was an enormous success. The Bishop took advantage of the marvelous good effected by his words and example, and sent him to Guadalajara to ease a dissension that was disturbing its citizens, and then on to several other places of his Diocese. Fatigued and infirm, Fr. Margil obeyed.

Truly it was a remarkable sight to see this saint still traveling barefoot, not so fleet of foot anymore, humble, worn and old, but shining every day more with a supernatural sheen, burning with zeal for souls. The people would go in procession to meet him as he entered a city, some traveling great distances, scattering branches of palms and flowers along the way.

When he reached Querétaro, he was so weak and emaciated it was obvious that death was near. As he traversed the streets of that city where he had done so much good, the people saw he would not be with them much longer and they cut pieces from his mantle to preserve them as holy relics. The Commissary General, fearing proper treatment was not available for him there, ordered him to go to Mexico City where he would have the advantages of an infirmary and the best medical attention.

Fr. Margil obeyed and set out on his last journey, a hundred miles he knew would shorten, not lengthen, his earthly days. On August 2nd, 1726, he arrived at Santa Cruz College and went to ask the blessing of the superior. “Rev. Father Superior,” he said, “the donkey has come here to deposit its burden.”

His illness lasted five days, but he never complained of sufferings or asked the least relief, although he suffered greatly. When sickness brought delirium, he was heard preaching, singing hymns, invoking the holy names of Jesus and Mary, reprimanding sinners with kindness and charity, and reciting the Rosary.

On August 5, when a picture of Our Lady of Remedies was brought to him, Fr. Margil greeted her with tender affection, and ended, “Hasta manana, my dearly beloved Lady, until tomorrow.” To keep his promise, the next day, the feast of the Transfiguration, his soul peacefully went to God between 1 and 2 o’clock in the afternoon. He died just 12 days short of his 69th year, having spent 53 years in the Franciscan Order and 43 years as a missionary in North and Central America.

Our Lady of the Remedies, Patroness of Valencia (Spain) |

When notice of his death was given, all the bells of the Mexico City began to ring announcing it. Citizens of all ages and conditions lined up to see the mortal remains of the Servant of God, exposed for three days in the Franciscan church and surrounded by guards to protect it from the multitudes. His face, pallid in life, had now assumed a rosy hue, his limbs remained flexible, his flesh warm. His feet, worn to leather and covered with rough calluses from the thousands of miles he had trod, became soft and supple like those of a child.

Even in death Fr. Antonio Margil continued to do good for souls. An artist of Mexico City who was contracted to make his portrait could not reproduce the countenance despite his efforts. Finally, the artist examined his conscience and found a serious sin he had never confessed. He made his confession to one of the fathers, received absolution, and was able to finish the portrait with the greatest ease.

Shortly after his death the process for beatification was begun. But because of grave political situation in Europe, the process was interrupted and only in 1836 was he declared Venerable by Pope Gregory XVI. The Franciscan martyrology commemorates Fr. Margil on August 6, the day of his death.

Why he is not a saint yet? In 1992 the archivist of the Vatican Congregation for Causes of Saints Fr. Jarslav Nemec and the Franciscan promoter of the cause, Fr. Juan Foquera, stated as soon as there is an approved miracle attributed to the intercession of Fr. Margil, he will be beatified, and then after a second miracle, he will be canonized. Miracles can be reported to The Margil House of Studies, in Houston, Tx

The grandeur of God is revealed in His saints

Before he died in Mexico City, he insisted on making a general confession, which was very short, since the faults of his lifetime were so slight that the confessor had difficulty finding sufficient matter to give him absolution. Seeing the surprise of the priest and fearing he would attribute the merit to him for such rare, spotless purity, Fr. Margil said:

“If Your Reverence should see a ball of gold suspended by a hair, though gold is very heavy, would you think that it was supported by itself? Now, I have been a poor creature, liable to fall at any moment, and if God had not kept his omnipotent hand over me, I do not know what I might have done.”

This conviction that all the good that came from him was due to God, and not himself, formed the foundation for the heroic humility he practiced.

The confessor also reported that he had questioned Fr. Margil about his experiences while saying Mass. With the greatest possible humility, he wrote, Fr. Margil told him a singular favor that he was wont to receive during Mass. After he spoke the words of the Consecration, Christ would seem to respond from the consecrated Host, using the same words of Consecration and alluding to the body of Fr. Margil, ‘Hoc est Corpus meum.’ This favor Fr. Margil attributed to the fact that he always had or tried to have Christ living within him.

Conclusion

The missionary efforts of Fr. Margil could be called diametrically opposed to the ecumenism introduced by Vatican II. With his burning zeal to bring all people to the Catholic faith, Fr. Margil would have been confounded by the meeting at Assisi, where Catholics met on an equal level with American Indian medicine men and African animists. For him, the Catholic Religion was the supreme value of life, the one truth all should profess. The false gods must be combated, the idols and superstitious charms burned.

The Missionaries converted the Indians and ordered all things to Catholic truth and morals. |

He understood that all the values of life are good to the measure that they serve the Catholic Church. So among the people he set out to evangelize, his first objective was to order everything to the Catholic faith. The customs, habits, ways of being that already existed among those people were good only in so much as they were ordered to the Catholic truth and morals. Those that were not ordered in this sense had to be put aside. This is the complete subjection of all things to the Catholic Religion, which is demanded by a truly saintly soul.

It is an honor to describe a little of the life of this extraordinary and saintly man, Fr. Antonio Margil. It is not by chance that part of the land he evangelized today is the United States, and especially Texas. Nothing happens by chance with Divine Providence.

What, then, is its significance? I leave the answer for each of my readers to discover. One thing is certain, from his place in Heaven, he is watching us, and he wants to help us to continue on or return to the true Catholic Faith, as he did with hundreds of thousands Indians in the New World. With this conviction I invite you to begin to pray to the glorious Ven. Antonio Margil de Jesus.

Click to purchase on tape or CD

Ven. Antonio Margil, Apostle of Texas

|

Margil Main Page | Religious Main

Page | Home Page | Books | CDs | Contact Us

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|