Art & Architecture

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two Ways of Seeing Country Life

It is six o’clock in the evening. The daily labor is finished. The noble tranquility of the atmosphere covers the vastness of the field, bringing repose and recollection. The gold twilight transforms nature, making a remote and suave reflection of the indescribable majesty of God shine in everything.

The toll of the Angelus bell is heard, muffled by the distance. It is the crystalline, material voice of the Church inviting the people to prayer. The peasants pray. They are two youths whose physiques express health and a longstanding habit of manual work. Their garbs are rustic. But their persons transmit the purity, elevation and natural delicacy of deeply Christian souls.

Their modest social condition is, as it were, transfigured and illuminated by their piety, which instills respect and sympathy for them. In their souls the splendorous golden rays of the sun are reflected, but the rays of a sun much higher than any other: the grace of God.

Truly, it is their beauty of soul that is the center of the picture, the highest point of aesthetic emotion. The countryside is beautiful, but it only acts as a background for the manifestation of the beauty of these souls united in prayer by the Son of God.

Nothing in these peasants indicates restlessness or malaise. They are fully conformed to their station in life, their profession, their class. What other dignity or happiness could this couple desire?

Jean-François Millet (1857-1859) admirably brought together on his canvas (L'Angélus - Musée d'Orsay - Paris) the necessary elements to understand the dignity of manual labor in the placid and happy atmosphere of true Christian virtue.

Not all moments of country life are like this. Millet caught, in what we would call a fortunate shot, a culminating moment of material and moral beauty. His picture has the merit of teaching men to see, amidst the routine of everyday rural life, a genuine and frequent glimpse of this Catholic physiognomy of persons and things in an ambience truly enlivened by the Holy Church.

Millet’s state of spirit, which he communicates to those who contemplate his masterpiece, is completely turned toward God and toward the reflection of the spiritual and material beauty that He projects in Creation.

For a psychological critique of this picture to be exact, it should only deplore a certain excess of sentimentalism.

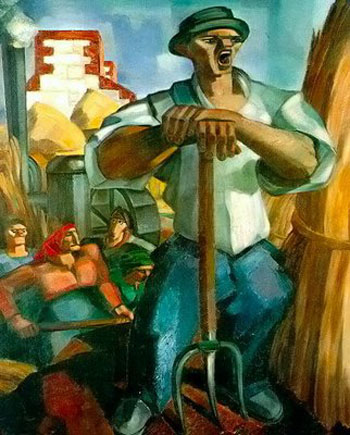

In this picture, it was not the spirit that dominated matter and ennobled it; it was matter that penetrated the spirit and degraded it. Physical labor has impressed on the bodies a brutality that could be called criminal. The faces exude a mood reminiscent of a vile tavern or concentration camp.

If the characters in the background were not so hardened, if they were capable of weeping, their tears would be of bitterness. If they were capable of moaning, their moans would be like grinding gears. The sadness, meanness and cacophony of colors, forms and souls exude from the mouth of the man in the foreground. It is not clear whether what he is shouting is a threat or a blasphemy.

Yves Alix portrayed, exaggerated and deformed to the point of delirium the aspects by which work is an expiation and suffering and earth is an exile. He expressed with meticulous fidelity - and with a kind of enthusiasm – what is most atrocious and low in the human soul in order to present the whole as a normal and real aspect of the spiritual and professional daily life of the worker.

Therefore, while a prayer exhales from the masterpiece of Millet, from the nightmare of Yves Alix a whiff of the revolution puffs out.

If God were to permit the Angels to beautify the earth and life, they would do so by making more frequent, durable and splendorous the aspects of nature that Millet observed and portrayed. If He were to permit the devils to disfigure man and creation, they would form – in the body, the soul and the appearances of things – personages and ambiences like those in the painting of Yves Alix.

Catolicismo n. 9, September 1951

Posted November 8, 2013

Posted November 8, 2013

______________________

______________________