|

Art & Architecture

Behind-the-Scenes in Modern Art

Cunha Alvarenga

We uphold that the movement called Modern Art is an aesthetic branch of one universal Revolution that aims to change the structure of human society, which also develops in the religious, political, social and economic spheres.

Elasticity by Umberto Boccioni, a Futurist artist |

Just as in the political sphere, agents from the left and the pseudo-right of the Revolution understand each other and work together for the totalitarian domination of society, so also in the aesthetic sphere the various schools of Modern Art converge and support one another.

This convergence of action and method can be verified in two important art currents at the beginning of the 20th century: Futurism representing the rightist Socialism, and Surrealism, the leftist Socialism. In both we find the same concern to establish dominance in society through magic, eastern mysticism, savage primitivism, a childish reasoning, madness, and a clownish spirit. In both we find the same obsession to annihilate the truth, reason, logic, order and everything they call bourgeois civilization.

The same goals

In both currents, Futurism and Surrealism, we find the same exaltation of intuition over reason. In this regard, the French philosopher Henri-Louis Bergson (1849-1951) revealed himself to be the philosopher par excellence of the Modern Art. He defended that a work of modern art should not have any rational or scientific explanation, but should be an immediate experience coming from the obscure region of the subconscious.

This erroneous presupposition was transferred to the political spectrum by another vanguard French thinker, Georges Sorel (1847-1922). His notion of the power of myth in people’s lives inspired both Nazis and Marxists. He wrote:

The Triumph of Surrealism by Max Ernst |

“Appeal must be made to collections of images which, taken together and through intuition alone, before any considered reflections are made, are capable of evoking the mass of sentiments that correspond to the different manifestations of the war undertaken by Socialism against contemporary society.” (2)

According to Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944), “the St. John the Baptist of Fascism,” as Mussolini called him, the Futurists should “promote hatred for intelligence and strive to awake that divine intuition, which is the gift characteristic of the Latin races.”

For this reason, in the Futurist exposition of Milan in 1911, along with the paintings of exponents of this current, works made by illiterates and children were exhibited, anticipating what would happen 40 years later at the São Paulo Art Biennale (1951) that bestowed awards on completely untrained “primitive” artists.

We find similar anti-establishment statements made by leaders of the Surrealist movement. For example, one of its founders Paul Éluard (1895-1952) announced: “We are conspiring to destroy the bourgeoisie and its ideal of goodness and beauty.”

One of the goals of these conspirators is to obliterate as much as possible legitimate manifestations of the human personality in art, because for both the Futurists as well as the Surrealists, “man has no more meaning than a stone.”

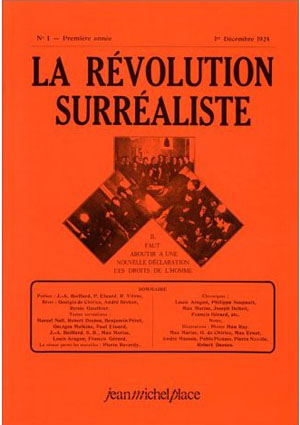

1st issue of The Surrealist Revolution, 1924 |

André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, stated: “We believe we can defeat reason and the bogus good sense. We sympathize with the revolutionary parties. We do not believe in human progress.”

French poet Louis Aragon (1897-1982), a Surrealist and a Communist, presents the following program: “To start, we will undermine the civilization so dear to you [bourgeois], where you have embedded your fossils.”

Just as members of Futurism dedicated themselves body and soul to promote a rightist Socialism, so the leaders of Surrealism, such as René Crevel, Salvador Dali, Paul Eluard and Marx Ernst, worked for a leftist Socialism. That group published a manifesto in 1924 in their periodical, Surrealism at the Service of the Revolution (Le Surrealism au Service de la Revolution), presenting Surrealism as aesthetics of liberation and defending Socialism. As part of their program, they aimed “to prepare the detour of the intellectual forces toward the revolution that is approaching.”

In this evaluation of the purposes and methods of different currents of Modern Art, we believe it will be helpful to briefly analyze the repercussions this European agitation of the artistic avant-garde caused in Brazil.

An uncomfortable forefather

Some art historians who write about events after the Week of Modern Art in São Paulo in 1922 try to deny Futurism’s influence on the art world. Further, they even try to hide the influence Modern Art has had. For example, Brazilian poet Murilo Araujo (1894-1980), an avant-garde writer, tries to downplay the influence of Dadaism when he writes:

“The Dadaists were simply seeking a naïve goal - the purity of little ones who play, the language da-da of children - because they were tired of the affected sophistication of civilization. In fact, we were and we are the opposite of this. We were already primitives and children, unsaturated with culture. We were da-daists since we were born.” (3)

The truth is we cannot write the history of Modern Art in Brazil without knowing the behind-the-scenes story of the leaders of this current both in Brazil or Europe.

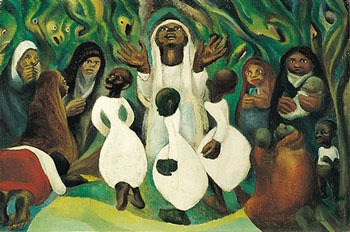

Brazilian primitive art exalted native black culture, above the Carnaval by Di Cavalcanti |

The driving force of the Week of Modern Art in São Paulo was Mario de Andrade (1893-1945), the central figure in the the ‘Group of the Five.’ Along with four other poets and artists - Oswald de Andrade, Menotti del Picchia, Tarsila do Amaral and Anita Malfatt - he was behind the 1922 event that reshaped both literature and the visual arts in Brazil.

Today, when almost all modern artists proudly consider themselves promoters of Communism, it is uncomfortable for them to acknowledge the strong presence of Futurism in the Week of Modern Art, since Futurism was tightly bound to Fascism, now a defeated ally.

However, poet Oswald de Andrade, one of the ‘Group of Five’ and not related to Mario de Andrade, testifies to the strong influence that both he and Mario de Andrade received from the Italian Futurism:

“In 1912, I went to France and came back with Marinetti’s Manifesto. By 1922, Mario de Andrade had works by all the Italian Futurists in his house. When Mario published Hallucinated City (Pauliceia Desvairada), it seemed to me a complete novelty. Mario carefully concealed from us the Italian Futurists he admired. When we better understood those Italian Futurists, the impression of novelty continued. The Italians gave Mario a formal model, which he used to create his own aesthetic experience. Further, I, who never knew how to make measured verse, found in it my opportunity to create my poetry. It was a liberated poetry.” (4)

Another curious fact is that painter Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, one of the Brazilian painters who presented his works in the Week of Modern Art, confessed 30 years afterward that it was the actual organizers of the event who orchestrated the hisses and heckling against themselves in order to give the impression that the public was rejecting them. They did this just to look like the European Dadaists who were booed by the public after the 1920 exposition of Cologne. In fact, the public were so enraged they also destroyed the works of art in the exposition. Max Ernst, their leader, interpreted that reaction as a success, since it supposedly reflected nothing but the bourgeois taste. So, the Brazilian modern artists arranged for a similar “success.”

Besides the ridiculousness of this staged episode, we have another confirmation of the same methods used by both the Futurists and the Dadaists.

Links with voodoo

Brazilian artists also began to imitate the European primitivism, one of the characteristics of Modern Art. In Brazil this tendency was translated into a supposedly “pure” primitive art that exalted the African element by exploiting the macumba (the Brazilian voodoo). Murillo Araujo reports his experiences with voodoo:

A macumba session celebrated in Modern Art |

“In 1924, I went to a session of macumba with some friends. The spectacle, at that time only known by the blacks who practiced the ritual, impressed us deeply. From it were born my black poems, the first of which was titled Macumba, published that same year."

It is interesting to point out that macumba was practiced by just a small number of blacks at that time. The majority of them had been harmonically integrated into the Catholic ambience of our country. In great part, it was this tendency toward primitivism promoted by modern artists that unfortunately re-directed the blacks to the demonic and barbarian rituals of their ancestors.

With this, we see how the aims of the avant-garde Modern Art movements coincide with those who want society to be dominated by black magic and voodoo in religion and by Socialism in politics.

1. Bergson was awarded the 1927 Nobel Prize in Literature in recognition of “his rich and vitalizing ideas and the brilliant skill with which they have been presented.” (Wikipededia, entry Henri-Louis Bergson)

2. Georges Sorel, Reflexions sur la Violence, p. 177.

3. Murilo Araujo, “Evolução e revolução modernistas,” Jornal do Comércio, May 10, 1953

4. Diário de Notícias, Rio, January 24, 1954.

Translated and adapted by TIA desk from

Catolicismo, n. 48, December 1954

Posted March 2, 2012

Related Topics of Interest

Vanguard Art against the Church Vanguard Art against the Church

The Modern Art's Kabala The Modern Art's Kabala

A Sacred Art Possesed by the Devil A Sacred Art Possesed by the Devil

Esoteric Characteristics of Modern Art Esoteric Characteristics of Modern Art

JPII: Animism Is Particularly Close to Christianity JPII: Animism Is Particularly Close to Christianity

Modern Art, Socialism & Marxism Modern Art, Socialism & Marxism

Two Pictures, Two Mentalities, Two Doctrines Two Pictures, Two Mentalities, Two Doctrines

Voodoo Mass in Pelotas, Brazil Voodoo Mass in Pelotas, Brazil

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Art & Architecture | Hot Topics | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|