American History

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

California's Protomartyr - Part I

Fray Luís Jayme:

First Martyr of California

Padre Luís Melchor Jayme (1740-1775)

Padre Luís Melchor Jayme (1740-1775) and his superior Padre Junípero Serra (1713-1784) had many similarities. Both hailed from the Island of Majorca in Spain and were the sons of farmers. Both were drawn early to the religious life and joined the Franciscan Order. Both became great scholars and taught philosophy at the Convento de San Francisco, the Majorcan motherhouse. Both had a great devotion to Ven. Mary of Agreda and avidly read her letter-plea for missionaries to the New World.

From the College of San Fernando in Mexico City, both Friars came to evangelize the natives of Alta California: At age 55, Friar Junípero, named President of the California Missions, led the Holy Expedition of 1769, which conquered for Spain the long coast of Alta, California, and founded the first nine of the 21 missions. (1) In 1771, the 31-year-old Fray Luís Jayme set out to become pastor of Mission San Diego de Alcalá, California’s first Mission, which would be his first and last assignment.

Both Friars ardently longed to give their lives as martyrs for the conversion of the native Indians. That burning flame would die with Padre Junípero at age 70 on his meager cot in Mission San Carlos Borromeo. It was Padre Jayme who won the martyr’s crown at age 35 in the year 1775 at Mission San Diego, where he was brutally massacred by rebellious Indians stirred up by pagan shamans, who had a special hatred for the priests.

Fray Jayme’s first assignment

The Yuman peoples of San Diego, where Fray Luís and his assistant Fray Vincente Furster were stationed in 1771, were the most treacherous and untrustworthy of all the coastal tribes. Notwithstanding, Friar Luís was well received by the Mission natives; he had a facility for language and had soon mastered the local Kumeyaay tongue and compiled a polyglot Catholic catechism.

The early San Diego Mission rebuilt after the attack; below, the Presidio looking at the San Diego Bay

In 1774, Fray Luís Jayme, realizing that the water was scarce at the Presidio (fort) and the influence of the soldiers disastrous to the new converts, had received permission from Fr. Junípero to move the Mission church quarters seven miles west to its present-day site. The hastily constructed Mission was particularly vulnerable to attack because, although it was only about seven miles from the Presidio, it lacked the usual protection of a palisade wall, essential for defense in case of an Indian attack.

Because the Mission was still too poor to house and feed all the converted Indians at the mission itself, many neophytes had to live in the nearby rancherías (native villages) with the still pagan families. In this less than ideal situation, many of the new converts resumed their bad customs and pagan practices.

Trouble brewing at San Diego Mission

After many exasperating delays, it had finally been decided to found Mission San Juan Capistrano – a halfway point between Mission San Diego and Mission San Gabriel. In October 1775, a party of missionaries and soldiers under the command of Lieutenant José Francisco Ortega set out to raise the Cross and begin the construction of the chapel and dwellings for the seventh Mission of Alta California.

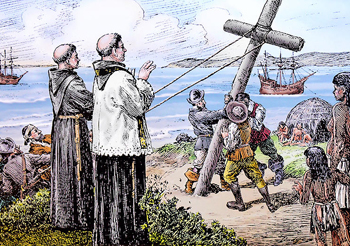

Lt. Ortega & his soldiers raising the Cross at the new mission site in San Juan Capistrano

On October 3, the vigil of the feast of St. Francis, a festive air permeated the Mission, where 60 Indians would receive Baptism, a ceremony that incited the fury of Satan and his minions, the witchdoctors. These shamans, who were keenly aware that their influence was rapidly diminishing, due to the apostolic zeal of the missionaries, saw an opportunity to be rid of their enemy. Two of the native chiefs, Carlos and Francisco, had recently been punished for a theft. Playing on their resentment and anger, the jealous shamans encouraged the disgruntled chiefs to leave the Mission and enter a plot of revolt.

The shamans, who governed by fear, hated the missionaries, who were winning the love & trust of the natives

In passing, let us note a well-known fact at play here: The Revolution never comes from the people. It is plotted by secret forces and directed by disgruntled leaders, who stir up resentments and play on the passions of the people.

The plan was to attack first the Mission to kill the missionaries and the handful of soldiers left to guard it, and then proceed to the Presidio, where a part of the rebellious warriors were stationed to stop the soldiers, should they come to the aid of the Mission during the attack.

The attack on the Mission

At about 1:30 on the night of the full moon of November 4, 1775, around 600-800 native warriors from some 40 rancherias silently crept into the Mission compound. They first surrounded the houses of the Christian Indians, threatening them with death should they try to warn the others. Then they plundered the church and sacristy, removing the statues and breaking open chests to snatch the coveted cassocks and stoles.

Where were the guards? In his account of the arson and massacre, Fray Fuster clearly states that “the sentinels were sound asleep.” Only when the natives, whooping and shouting, set fire to the church and nearby buildings did the commotion and crackling of flames awaken the two missionaries and the guards.

Upon seeing the danger, Fray Furster ran to the soldier’s barracks where the guards were already firing their muskets. The carpenter Urcelino, who was sleeping in the barracks, had taken a musket to assist in the defense, but he was shortly pierced by an arrow. He cried out: “Aye! Indian who has killed me, may God forgive you!” He died five days later in a good state of soul, always pronouncing his pardon of the attacker and leaving his earthly goods to the San Diego Indians.

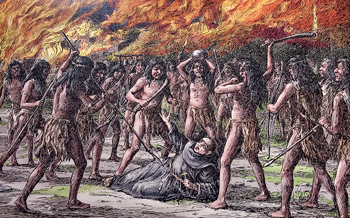

The enraged Indians dragged the Padre to the creek bed & brutally killed him

They seized the Padre, dragged him to the nearby arroyo, and stripped off his garments and the relic of a Saint he wore around his neck. They shot 18 arrows into his body, eight of which were mortal, and then pulverized his face and body with clubs and stones. They left the now unrecognizable body in the water bed.

The attack on the Mission continued through the night. At the Presidio the guards were also sleeping and, despite the loud cries and blazing fire, failed to awake or come to the aid of the beleaguered band at the Mission. In his report of the assault, Fray Fuster noted the strange sleep that had overtaken the sentinel at the military post: “Without doubt, the sentinel had been sleeping, since he neither had seen the great fire, although from the Presidio the Mission buildings are visible, nor had even heard the gunshots so often breaking the silence of the night, although at the Mission one could hear the salute which was fired every morning at the Presidio.” (3)

Fr. Furster made a plea for Our Lady’s protection

The flames soon forced them to flee again, this time to the partially burned adobe kitchen structure. Before the Spaniards had succeeded in barricading this opening with chests and a huge copper kettle, every man had been wounded. But Corporal Rocha continued a steady firing, with the blacksmith and wounded soldiers rapidly loading and reloading muskets passed to him.

Fray Fuster implored mercy through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin to allow them to be victorious, and promised to fast on nine Saturdays and celebrate nine holy Masses in her honor should she grant this favor. The soldiers there also offered to fast and hear the Masses offered.

Fray Fuster recorded: “And it seems the Holy Mother sensibly heard our supplications, for many times I took burning firebrands right off the top of the powder bag.” (4) Further, during this last stand behind the makeshift adobe walls, although the natives were only a short distance from the beleaguered group, not one of the arrows or stones touched them. (5)

In early dawn, a well-aimed shot from a musket suddenly sent the horde fleeing in panic, and the light of day finally appeared over the burned out Mission San Diego. The survivors rejoiced and thanked Our Lord and His Blessed Mother for protecting their lives in the battle where they were so vastly outnumbered.

Continued

The campanile of San Diego Mission

- The nine missions Padre Serra founded: 1. (1769) Mission San Diego de Alcalá; 2. (1770) Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo; 3. (1771) Mission San Antonio de Padua; 4. (1771) Mission San Gabriel; 5. (1772) Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa; 6. (1776) Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores); 7. (1776) Mission San Juan Capistrano; 8. (1777) Mission Santa Clara de Asís; 9. (1782) Mission San Buenaventura.

- Francisco Palau, Life and Apostolic Labors of the Ven. Father Junipero Serra, George Wharton James, 1913, p.173.

- Fr. Zephyrin Engelhardt, OFM, San Diego Mission, Aan Francisco: James H. Barry Co, 1920, p. 64.

- Maynard Griger, The Life and Times of Junípero Serra, vol. II, Washington: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, p. 64<./li>

- Fr. Zephyrin Engelhardt, San Diego Mission, p. 66.

Posted July 21, 2025

______________________

______________________