|

American History

Our Lady of Bethlehem - Part II

She Begins to Conquer California

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

Packed in the cargo of the San Antonio, the life-size statue of Our Lady of Bethlehem left the port of La Paz in Mexico to begin her journey north to San Diego, where the Presidio-Mission would be established in Alta California. Fr. Junipero Serra left by land to meet them there; then the Holy Expedition would continue up to Monterey to establish Mission San Carlos.

On March 28, 1769, accompanied only by two guards and a Spanish attendant, Fr. Serra set out from La Paz to begin the 95-day, 750 mile journey north to San Diego. They moved “at a pack train pace,” averaging only four hours travel per day due to the friar’s inflamed leg, which was swollen to the middle of the calf and covered with abcesses. (1)

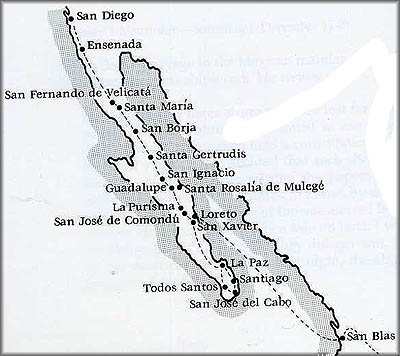

The land route followed by Fr. Serra to San Diego |

On May 7, they met the main body of the expedition led by Governor Portolá at Mission Santa Maria, still in Baja California (see map). He writes, “We were as happy as possible to see each other, all eager to start on our new venture across the desert.”

Fifty miles north of Santa Maria Mission, the contingency stopped at the frontier outpost of San Fernando at Velicatá. That Pentecost Sunday, May 14, was a day of great joy for Fr. Serra, for here he blessed and erected the cross to establish the first Indian mission of the expedition.

As the group prepared to travel north for San Diego, Fr. Serra found he could hardly stand, so inflamed was his leg. As a last alternative to being carried on a stretcher, Serra asked the muleteer to prepare the same poultice he used for his animals and apply it to his leg. The next morning, his leg was so improved he could say Mass and continue the journey walking. Although Fr. Serra considered it “a matter of little moment,” the group considered it nothing short of a miracle.(2)

The first Mission of California is founded

Spain established its first mission-presidio in Alta California atop this hill |

As they traveled, the terrain changed. The naked hills and stony deserts were replaced with grassy valleys and verdant vegetable life. Fr. Serra describes the Indians they met along the way as talented in the craft of pottery and gentle. He considered it a good sign that the savages loved dress goods, and “would jump in the fire to get a piece.” (3)

On Saturday, July 1, 1769, the land expedition reached San Diego and faced a gloomy situation. The San José, the last ship of the expedition to sail from La Paz, was shipwrecked; the San Carlos had been struck by pestilence and all of two of its sailors were dead. The third, the San Antonio – which carried the statue of Our Lady of Bethlehem – had been the first to arrive and was sound, but now its men were falling ill from the scurvy as well.

Undaunted, Portolá continued with the plan. On July 9 the San Carlos with its diminished force of crew and soldiers set out on a scouting mission to find Monterey Bay. A few days later, the San Antonio, having unloaded its precious treasure of the statue of Our Lady of Bethlehem to preside over the new Mission on Presidio Hill, hoisted sail for San Blas to obtain more seamen and supplies, leaving only eight soldiers behind with Fr. Serra.

The life size statues of Our Lady and the Infant captured the hearts of the Indians |

On July 16, 1769, Fr. Junipero Serra planted the traditional great cross on a hillock overlooking the harbor and said Mass under a canopy of twigs. Spain thus established its presence in present-day California atop Presidio Hill with the official founding of Mission San Diego de Alcalá. Our history books tell us that this Mission, called the Mother of the Missions, is the first of the State’s 21 missions. What they fail to report, however, is that Our Lady of Bethlehem was there from the outset. Into that first humble chapel of Mission San Diego her statue was placed, and here she would reign for one year.

From the start, this Mission was the most difficult. The Kumeyaay Indians of the San Diego region were aggressive, thievish and arrogant, different from the other mild-mannered tribes of Alta California. Aware of the weakened condition of the camp, a group of about 30 Indians attacked the Mission on August 15, the Feast of the Assumption.

The savages thought it would be an easy matter to dispose of few soldiers and friars, but did not reckon with either the determination of that small group or the protection of Our Lady. In the fight, only one Spaniard was killed and three wounded; the Indians lost five with many wounded.

A few days later, the Indians came to sue for peace and asked care for their wounded. The expedition doctor, himself still recovering from scurvy, cured them all. Thenceforth, they presented themselves at the Mission unarmed. The Indian women in particular were eager to visit the Mission.

Fr. Serra reports that they were taken with the life-size Our Lady of Bethlehem and the Infant Child. Thinking the mother very pale and emaciated, they would bring food for her and the Infant; in their simplicity, some of the women even clamored to suckle the Christ Child. (4) The work of Our Lady in California had begun.

A threat to end the Holy Expedition

Although there were no more Indian attacks, the fledging Mission was in a dire situation. After six months, supplies were low and there was no sign of either the packet ship San Antonio or of Governor Portolá. The Indians showed no interest in conversion.

On January 24, 1770, Portolá finally returned, bearing his own bad news. Monterey Bay, described so precisely in the annals of Sebastian Vizcaíno in 1603, had eluded the quest. The only good news was that further north another very beautiful bay had been discovered and christened San Francisco.

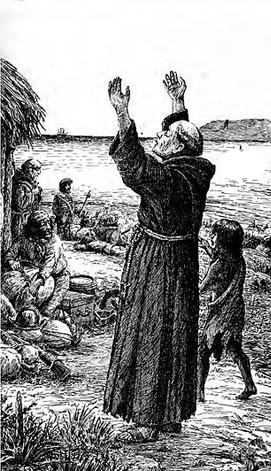

Fr. Serra rejoices at the sight of the San Antonio entering San Diego Bay on March 19, 1770 |

Fr. Serra, certain that the Monterey harbor existed, wanted the Holy Expedition to continue as planned. Governor Portolá was not so sure. With food to last only until the end of April, he decided that if a supply ship arrived at San Diego before March 14, he would immediately set out for Monterey. If not, they would all leave for Baja California on the 15th. Serra asked that the date of withdrawal be postponed until March 19, the feast of St. Joseph - patron of the Expedition. Portolá granted the extra days, postponing departure until the 20th.

Fearing that decades would pass before more friars were sent to convert the Indians, Fr. Serra had already decided to remain there even if the settlement was abandoned. A novena to St. Joseph was begun, and many hours were spent before Our Lady of Bethlehem, beseeching her help to save the Holy Expedition.

That help came, but only at the last hour. Just before sunset on the 19th, Fr. Serra, who continued to watch the ocean, caught sight of a ship and the San Antonio entered the harbor. When the ship landed and the circumstances of its landing were learned, all recognized the hand of Providence. The ship had not planned to put into port at San Diego. It was bound for Monterey, since it was believed that Portolá was already there awaiting supplies. It had already passed the San Diego harbor when it lost one of its anchors and was forced to turn around and make port there for repairs.

The Expedition was saved. For the rest of his life, Fr. Serra celebrated a High Mass of Thanksgiving on the 19th of each month. The two ships were outfitted and in Easter week of April 1770, they set out for Monterey. This time the San Antonio carried Fr. Junipero Serra and Our Lady of Bethlehem.

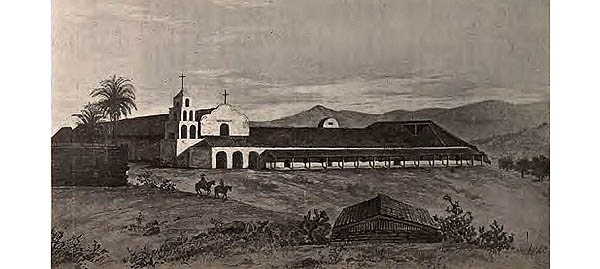

The Presidio-Mission San Diego in 1848, before the United States cavalry

took over California and used the church for barracks and a stable |

1. Martin Morgado, Junípero Serra’s Legacy, Pacific Grove, CA: Mount Carmel, 1987, p. 23.

2. Ibid., p. 39.

3. Ibid., p. 31-32.

4. Omer Englebert, The Last of the Conquistadors, Junipero Serra 1713-1784, New York: Harcourt, Brace. Place of Publication, 1956, p. 82.

Continued

Posted September 23, 2011

Related Topics of Interest

Our Lady of Bethlehem - I- Her Adventure in America Our Lady of Bethlehem - I- Her Adventure in America

The Appeal of the Stones San Juan Capistrano The Appeal of the Stones San Juan Capistrano

La Conquistadora: Our Country's Oldest Madonna La Conquistadora: Our Country's Oldest Madonna

The Burning of the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown The Burning of the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown

Let None Dare Call it Liberty Let None Dare Call it Liberty

Mary of Agreda in America Mary of Agreda in America

The Cabalgata of Christ the King The Cabalgata of Christ the King

Related Works of Interest

|

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|