World History

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The French Revolution - II

The Religious Roots of the French Revolution

As noted in the previous article, the French Revolution did not appear suddenly as a spontaneous reaction of an angry, oppressed people. The ground had been carefully prepared by revolutionaries for a furious eruption against the Monarchy and the Church.

Many historians pretend that religion had nothing to do with the French Revolution. The argument that a revolution that turned so violently against Catholicism had no religious origins is either

biased or naïve.

Many historians pretend that religion had nothing to do with the French Revolution. The argument that a revolution that turned so violently against Catholicism had no religious origins is either

biased or naïve.

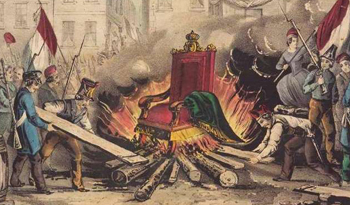

Flashing back in History, we see that Puritanism dealt a strong blow to the Monarchy of England during the so-called Glorious Revolution, which beheaded the King and established a Constitutional Monarchy. (1) The French Revolution went several steps further: It not only committed regicide as well, but it tried to abolish Christianity entirely.

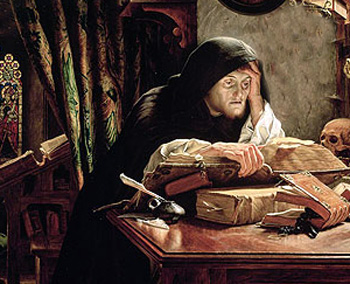

I believe that the more remote religious cause of the French Revolution was Protestantism.

Protestantism: Equality in religion leads to equality in government

It was the Protestant Revolution of the 16th century that broke the unity and equilibrium of Christendom.

Luther rose up against the Papacy, denying the hierarchical and monarchical character of the Church by proclaiming the ‘priesthood of all believers.’ He also affirmed the principle of equality and applied it in the religious sphere calling for the free examination of Scripture. (2)

Luther rose up against the Papacy, denying the hierarchical and monarchical character of the Church by proclaiming the ‘priesthood of all believers.’ He also affirmed the principle of equality and applied it in the religious sphere calling for the free examination of Scripture. (2)

Once equality is affirmed as a good in itself, then the next step is to apply it in all aspects of human life. It is natural, then, that some sectarians of Luther should take those principles to their final consequence. Calvin applied the idea of equality in a an even more radical way. While Luther only rejected papal authority and accepted bishops, Calvin only accepted the priesthood. In politics, Luther still would favor absolutism. Calvin was a republican already against the monarchy.

The Anabaptists, part of the Radical Protestant Revolution, went even further. They wanted complete equality, not only in religious matters but in the economic sphere as well. They also called for full liberty of conscience. Thus in them the French Revolution was already fully present.

Led by Thomas Munster (c. 1489–1525), the Anabaptists not only called for an end to the monarchy, but imposed a communist regime on the city of Muhlhausen. The monasteries were seized, and all property was decreed to be in common. The consequence of the latter, as a contemporary observer noted, was that “this so affected the folk that no one wanted to work.” (3) Essentially, Anabaptism is Protestantism taken to its final conclusion.

Led by Thomas Munster (c. 1489–1525), the Anabaptists not only called for an end to the monarchy, but imposed a communist regime on the city of Muhlhausen. The monasteries were seized, and all property was decreed to be in common. The consequence of the latter, as a contemporary observer noted, was that “this so affected the folk that no one wanted to work.” (3) Essentially, Anabaptism is Protestantism taken to its final conclusion.

Two centuries later, the French Revolution applied to the political arena the same ideas that Luther had established in the religious sphere.

Protestantism broke the unity of the medieval Catholic Church and wanted to do away with the ecclesiastical hierarchy, especially the Papacy.

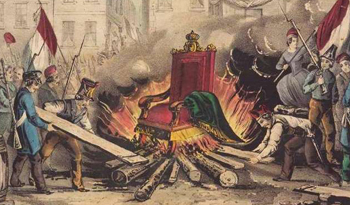

The French Revolution was no more than the transposition of those same egalitarian principles onto the political sphere. That is to say, first it was necessary to break the Papal Monarchy and to impose equality of religion, and then the next step came, the breaking of the temporal Monarchy and the imposition of the Republic.

Prof. Plinio describes how French Revolution corresponds to the Protestant Revolution in his landmark work

Revolution and Counter-Revolution:

Prof. Plinio describes how French Revolution corresponds to the Protestant Revolution in his landmark work

Revolution and Counter-Revolution:

Jansenism

In the 17th and 18th centuries Jansenism appeared chiefly in France, the Low Countries and Italy. In France it gradually became connected with the struggle against the Papacy, joinging together with proponents of Gallicanism, which also advocated restriction of papal power. To understand the role of Jansenism in the French Revolution, one much realize that there are really two phases of this supposed “reform” movement in the Catholic Church of France: The first is religious, the second, political.

Its religious first phase

Jansenism takes its name from Cornelius Jansenius, a Dutch theologian who died in 1638. His writings gave rise to a complex religious movement in Catholic thought and practice that prevailed, principally in France, in the 17th century.

Its adherents adopted a view of Original Sin, grace and predestination that they claimed came from the teachings of St. Augustine but was ultimately condemned by the Church. (4) The Jansenists essentially rejected free will and man’s ability to cooperate with God’s grace.

Their pessimistic view led them to teach that most people, even those free from mortal sin, were unworthy to receive Communion. They also opposed what they considered the undue emphasis on the cults to the Sacred Heart and the Virgin Mary, which they considered innovations.

In some of its representatives, Jansenism also opposed Our Lady’s Immaculate Conception and denied her bodily Assumption and Queenship in Heaven.

Its political second phase

By the 18th century, the emphasis of Jansenism had left the religious sphere – although leaving its strong cold Calvinist-style mark – and had shifted to the political sphere.

Jansenism came to include nationalist aims, calling for the independence of the French Church from Rome’s control. Its political proponents challenged the Papal primacy over the French Church, as well as the subordination of parish priests to higher clergy. (5)

This translated in the political sphere to a revolt against the absolute monarchy of the King. The Jansenists thus came to offer strong support for the constitutional novelties that the Revolution wanted to impose.

This translated in the political sphere to a revolt against the absolute monarchy of the King. The Jansenists thus came to offer strong support for the constitutional novelties that the Revolution wanted to impose.

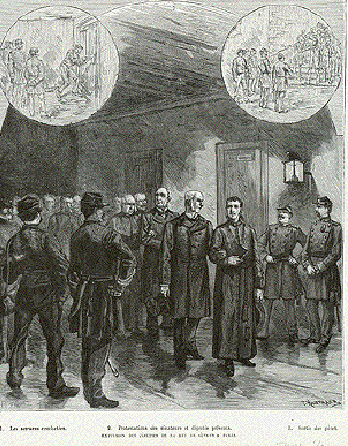

They also clashed with the Jesuits, who supported the Pope’s condemnation of their doctrine, and they played a large role in expelling the Jesuit Order from France. (6) Thus Jansenism helped to undermine the stability of the Old Regime and the traditionalist elements of the Church.

Jansenism spread so much among the French clergy that it can be affirmed that through its influence, the French Revolution can be called a Jansenist Revolution. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which expresses well the spirit of the French Revolution, was the work of Jansenists and Gallicans.

In summary, the Jansenists defended the following ideas that strongly influenced the revolutionary ideology:

Gallicanism

The French Catholic Church, known as the Gallican Church, traditionally recognized the authority of the Pope as head of the Catholic Church, but had negotiated certain liberties that privileged the authority of the French Monarch. Titled the Most Christian King, the King in turn was guarantor of the Catholic Faith.

The French Catholic Church, known as the Gallican Church, traditionally recognized the authority of the Pope as head of the Catholic Church, but had negotiated certain liberties that privileged the authority of the French Monarch. Titled the Most Christian King, the King in turn was guarantor of the Catholic Faith.

However, Protestantism in France produced the birth of a more radical Gallican sect, which called for the complete independence of the French Church from the Pope in Rome. This attitude was part of the heresy of Gallicanism, which held that ecumenical councils and the local church have greater authority than the Pope.

The Gallicans united with the Jansenists in their fight against the Jesuits, loyal defenders of the Papacy and the Monarchy in France. Both Gallicans and Jansenists supported the constitutional principles of the French Revolution. Thus both prepared the ground for the 1789 Revolution.

To be continued

Many historians falsely present the ‘people’ as instigators of the French Revolution

Flashing back in History, we see that Puritanism dealt a strong blow to the Monarchy of England during the so-called Glorious Revolution, which beheaded the King and established a Constitutional Monarchy. (1) The French Revolution went several steps further: It not only committed regicide as well, but it tried to abolish Christianity entirely.

I believe that the more remote religious cause of the French Revolution was Protestantism.

Protestantism: Equality in religion leads to equality in government

It was the Protestant Revolution of the 16th century that broke the unity and equilibrium of Christendom.

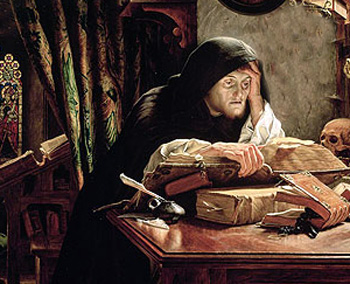

Luther studying to justify his ‘sola fidei’ thesis

Once equality is affirmed as a good in itself, then the next step is to apply it in all aspects of human life. It is natural, then, that some sectarians of Luther should take those principles to their final consequence. Calvin applied the idea of equality in a an even more radical way. While Luther only rejected papal authority and accepted bishops, Calvin only accepted the priesthood. In politics, Luther still would favor absolutism. Calvin was a republican already against the monarchy.

The Anabaptists, part of the Radical Protestant Revolution, went even further. They wanted complete equality, not only in religious matters but in the economic sphere as well. They also called for full liberty of conscience. Thus in them the French Revolution was already fully present.

Thomas Munster took the Protestant Revolution to its final consequences with his Anabaptist sect

Two centuries later, the French Revolution applied to the political arena the same ideas that Luther had established in the religious sphere.

Protestantism broke the unity of the medieval Catholic Church and wanted to do away with the ecclesiastical hierarchy, especially the Papacy.

The French Revolution was no more than the transposition of those same egalitarian principles onto the political sphere. That is to say, first it was necessary to break the Papal Monarchy and to impose equality of religion, and then the next step came, the breaking of the temporal Monarchy and the imposition of the Republic.

Revolutionaries loot & destroy the royal throne

- The revolt against the King corresponded to the revolt against the Pope;

- The revolt of the common people against the nobles corresponded to the revolt of the common laymen against the “aristocracy” of the Church, the clergy;

- The affirmation of popular sovereignty, or the sovereignty of the people corresponded to the Protestant “priesthood of all believers,” which insists that all baptized believers were on an equal footing;

- The free-examination that was accepted in the religious sphere by Protestantism generated the exaltation of reason and the free-thinking of the Enlightenment, which paved the way for the French Revolution. (Part I, Chap. 3, 5.C The French Revolution)

Jansenism

In the 17th and 18th centuries Jansenism appeared chiefly in France, the Low Countries and Italy. In France it gradually became connected with the struggle against the Papacy, joinging together with proponents of Gallicanism, which also advocated restriction of papal power. To understand the role of Jansenism in the French Revolution, one much realize that there are really two phases of this supposed “reform” movement in the Catholic Church of France: The first is religious, the second, political.

Its religious first phase

Jansenism takes its name from Cornelius Jansenius, a Dutch theologian who died in 1638. His writings gave rise to a complex religious movement in Catholic thought and practice that prevailed, principally in France, in the 17th century.

Its adherents adopted a view of Original Sin, grace and predestination that they claimed came from the teachings of St. Augustine but was ultimately condemned by the Church. (4) The Jansenists essentially rejected free will and man’s ability to cooperate with God’s grace.

Their pessimistic view led them to teach that most people, even those free from mortal sin, were unworthy to receive Communion. They also opposed what they considered the undue emphasis on the cults to the Sacred Heart and the Virgin Mary, which they considered innovations.

In some of its representatives, Jansenism also opposed Our Lady’s Immaculate Conception and denied her bodily Assumption and Queenship in Heaven.

Its political second phase

By the 18th century, the emphasis of Jansenism had left the religious sphere – although leaving its strong cold Calvinist-style mark – and had shifted to the political sphere.

Jansenism came to include nationalist aims, calling for the independence of the French Church from Rome’s control. Its political proponents challenged the Papal primacy over the French Church, as well as the subordination of parish priests to higher clergy. (5)

Clement XI's Bull Unigenitus (1713) condemned Jansenist teachings & its political influence

They also clashed with the Jesuits, who supported the Pope’s condemnation of their doctrine, and they played a large role in expelling the Jesuit Order from France. (6) Thus Jansenism helped to undermine the stability of the Old Regime and the traditionalist elements of the Church.

Jansenism spread so much among the French clergy that it can be affirmed that through its influence, the French Revolution can be called a Jansenist Revolution. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which expresses well the spirit of the French Revolution, was the work of Jansenists and Gallicans.

In summary, the Jansenists defended the following ideas that strongly influenced the revolutionary ideology:

- The abolition of papal authority;

- The democratization of the Church through the election of bishops and priests by the people;

- The formation of a national church.

Gallicanism

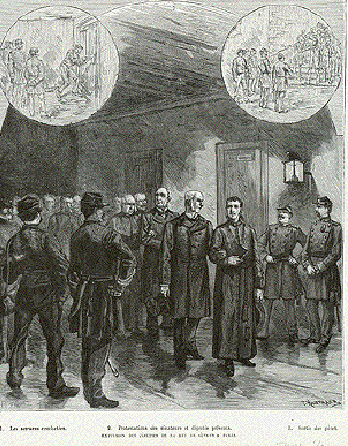

The Jesuits were expelled from France through the efforts of the Gallicans & Jansenists

However, Protestantism in France produced the birth of a more radical Gallican sect, which called for the complete independence of the French Church from the Pope in Rome. This attitude was part of the heresy of Gallicanism, which held that ecumenical councils and the local church have greater authority than the Pope.

The Gallicans united with the Jansenists in their fight against the Jesuits, loyal defenders of the Papacy and the Monarchy in France. Both Gallicans and Jansenists supported the constitutional principles of the French Revolution. Thus both prepared the ground for the 1789 Revolution.

To be continued

- The English King Charles I provoked great hostility from Parliament, which was dominated by Puritans. In 1642, a civil war began between the supporters of Charles, called Cavaliers, and the Puritan supporters of Parliament. The Puritans, led by Oliver Cromwell, defeated Charles in 1648 and beheaded him.

- As Prof., Plinio Correa de Oliveira notes in his landmark work, Revolution and Counter-Revolution, pride begot the spirit of doubt and the free examination of Scripture.

- Murray N. Rothbard, Messianic Communism in the Protestant Reformation, Mises Institute, https://mises.org/library/messianic-communism-protestant-reformation

- In 1713 the papal bull Unigenitus of Sept. 8, 1713, Pope Clement XI condemned Jansenist doctrines, as well as certain tenets of Gallicanism. This Bull placed the French Jansenists on a trajectory ending in the rejection of revealed religion in general and the promotion of the French Revolution. “The Religious Origins of the French Revolution, 1560–1791” in The Origins of the French Revolution, Yale Un Press: 1996, pp.160-190.

- “Jansenism,” on LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOUTION, https://revolution.chnm.org/d/1095.

- Adam Hunt, “Suppressing the Arbitrary: Political Jansenism in the French Revolution and the Abolition of Lettres de Cachet, 1780-1790”, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/w/wsfh/0642292.0045.002/--suppressing-the-arbitrary-political-jansenism-in-the-french?rgn=main;view=fulltext

Posted November 24, 2023

______________________

______________________